You are here

How Are Samuel the Lamanite and the Biblical Prophet Samuel Similar?

Helaman 13:3

The Know

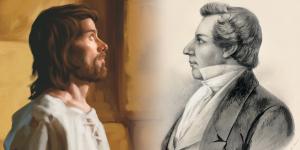

Samuel the Lamanite was likely not what the Nephites expected from a prophet of the Lord. He was a Lamanite, he came from outside their established institutions, and he proclaimed God’s ire in a radically public demonstration. Yet, Samuel is also everything to be expected of a biblical prophet. He quoted extensively from previous prophecies, preached against societal wickedness, and had the spirit of revelation. Scholars have compared Samuel the Lamanite to several other biblical prophets, but in addition much can be learned from comparing Samuel to his namesake, Samuel of the Old Testament.1 Both Samuel the Lamanite and the biblical Samuel had similar prophetic calls, foretold a coming Messiah, wielded God’s sword of justice, and subverted societal expectations.

They Both Shared the Same Meaningful Name

Both Samuel the Lamanite and the biblical Samuel began their stories with the same wordplay on their names. Hannah named her miracle son Samuel because, “I have asked him of the Lord” (1 Samuel 1:20). Here Hannah was likely playing off Samuel’s name which sounds like the Hebrew phrase “heard of God.”2 Hannah’s heart-wrenching struggle with infertility prompted her to petition God for a son to serve the Lord, and the Lord heard her cries. A similar theme is picked up again in chapter 3, when Samuel begins his training with Eli the priest. Upon mistaking the voice of the lord three times in succession, Samuel finally recognized God’s voice and declared, “Speak; for thy servant heareth” (1 Samuel 3:10).

As for Samuel the Lamanite, his story similarly opens up with themes of hearing and not hearing words. After Samuel preached at Zarahemla for many days, the Nephites there cast him out of the city, signaling their refusal to listen any longer to his prophetic words. Then immediately afterward, Samuel hears the “voice of the Lord” telling him to “return again, and prophesy unto the people” (Helaman 13:3). In rich irony, the chosen Nephites refused to hear the voice of the Lord because of “the hardness of the hearts” (v. 8), while Samuel heard the Lord so intimately that he was able to prophesy “whatsoever things the Lord put into his heart” (v. 4).

They Both Foretold a Future Messiah

One of the things the biblical prophet Samuel is most famous for is anointing Israel’s first kings. Through revelation from the Lord, Samuel anointed Saul as the first ruler of Israel (1 Samuel 10:1). Then, upon Saul’s disobedience, Samuel anointed a young shepherd boy, David, to become Israel’s future king (1 Samuel 16:13). In that fateful act, Samuel established a future messiah, since “messiah” means “anointed one” in Hebrew.

Samuel the Lamanite prophesied of a future messiah even more explicitly. As instructed by an angel, Samuel told the people to “prepare the way of the Lord” (Helaman 14:9), who would bring everlasting life, salvation, reconciliation from the fall, and resurrection to all who would believe on his name (vv. 2, 8, 12, 15–17). The sacred name of the Messiah would be “the Son of God, the Father of heaven and of earth, the Creator of all things from the beginning” (v. 12), a royal title befitting a king.3 Samuel the Lamanite helped prepare the way of the future king by preaching repentance and prophesying the signs of His birth and death.

They Both Wielded the Sword of God’s Justice

In dramatic fashion, Samuel the Lamanite began his famous speech by stretching forth his hand and declaring that God’s “sword of justice” was hanging over the Nephites and would fall swiftly if they would not repent (Helaman 13:5). We might imagine that Samuel’s outstretched hand, hanging over the people from his elevated position atop the wall, symbolically mirrored the wrathful hand of God, holding the sword of justice over the hardened people.4

A similar motif plays out in the biblical Samuel’s story. When King Saul disobeyed the Lord’s commands to destroy all the Amalekites, the biblical prophet Samuel wielded a literal sword to execute the Lord’s orders against Agag, the king of the Amalekites (1 Samuel 15:33). When Samuel killed king Agag with the sword, he ultimately decided Saul’s fate of losing the monarchy, making way for David to become king. Similarly, Samuel metaphorically wielding God’s sword of justice can be seen as the hinge point for the Nephites losing their covenant status, ultimately being destroyed, and making way for the new king, Jesus Christ.5

They Both Subverted Erroneous Expectations

Finally, both Samuel the Lamanite and the biblical Samuel broke down barriers and subverted societal expectations. As a young boy, the biblical Samuel trained under a priest named Eli who served in the Israelite tabernacle. Yet even though Eli was supposed to be the sagacious spiritual guide for Israel, it was the boy Samuel upon whom the Lord repeatedly called and to whom the Lord revealed His will. (1 Samuel 3:1–10).

Samuel the Lamanite’s identity is wrapped up in the only descriptor the reader has about him: “a Lamanite.” He was an outsider, and Lamanites in particular were not people to whom the Nephites looked for religious guidance. The Nephites, being lifted up in the pride of their hearts, may have assumed that they were God’s chosen, covenant people, and so were the only source of spiritual light. Just as the biblical Samuel unexpectedly heard and hearkened to the voice of the Lord in his youth, Samuel the Lamanite heard and preached the word of the Lord to the Nephites, against all expectations of the established covenant community.

The Why

All of this highlights how Samuel the Lamanite and Samuel the Israelite both fulfilled archetypal traits of true biblical prophets. They spoke with God’s words, had a revelatory prophetic call, used prophetic gestures, proscribed current wickedness, and foretold of a coming messiah. Samuel the Lamanite fulfilled the role of a righteous, biblical prophet, in direct opposition to the expectations of the Nephites.

These details help us see that Samuel the Lamanite was not a youthful novice in the gospel. When Samuel stretched forth his hand as a gesture of speech, he mirrored both Abinadi and Nephi. These Nephite prophets used this gesture to invoke the sacred power of God to protect them from harm. By using this gesture Samuel assumed the Nephite prophetic mantel and was miraculously protected from the stones and arrows of the angry Nephites.6

In his discourse to the Nephites, Samuel also exemplified full biblical prophethood in the way he quoted and alluded to past prophets. He used scriptural language akin to Isaiah, Ezekiel, Jeremiah, Psalms, and even John the Baptist.7 Like John the Baptist, Samuel was not part of the institutional hierarchy, but was an alienated voice in the wilderness, sent to prepare the way of the Lord. Like many prophets before him, Samuel invoked God’s voice with the archetypal phrase, “thus saith the Lord,” implying Samuel’s own admission into God’s divine council.8 Samuel also made massive use of prophecies given by Nephi, Jacob, Benjamin, Alma, and by his missionary and mentor Nephi the son of Helaman.9

Whom the Lord calls He clearly qualifies. Though he was called at first as a young boy, Samuel in Israel became a powerful prophet. Likewise, Samuel the Lamanite’s testimony is emblematic of how the Lord calls whom He will. The Nephites would hardly have expected a Lamanite to deliver to them such an important prophetic speech. Yet the Lamanites as a people were unexpectedly more righteous than the Nephites. Readers can appreciate the importance of not assuming righteousness or virtue based on someone’s group affiliation or preconceived notions. Skin color, covenant, or economic prosperity ultimately are of no consequence to the Lord when compared to someone’s personal righteousness. Samuel’s teachings were so important (and apparently overlooked by the Nephites), that Jesus Christ Himself commanded Samuel’s prophecies to be restored to the Nephite records (see 3 Nephi 23:7–13). In perfect congruence with a principle taught to the biblical Samuel, the story of Samuel the Lamanite strikingly shows how “the Lord seeth not as man seeth; for man looketh on the outward appearance, but the Lord looketh on the heart” (1 Samuel 16:7).

Further Reading

Book of Mormon Central, “Why did Samuel Rely So Heavily on the Words of Past Prophets? (Helaman 14:1),” KnoWhy 185 (September 12, 2016).

Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Abinadi Stretch Forth His Hand as He Prophesied? (Mosiah 16:1),” KnoWhy 94 (May 6, 2016).

Shon Hopkin and John Hilton III, “Samuel’s Reliance on Biblical Language,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 24 (2015): 31–52.

- 1. See Shon Hopkin and John Hilton III, “Samuel’s Reliance on Biblical Language,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 24 (2015): 31–52; Quinten Barney, “Samuel the Lamanite, Christ, and Zenos: A Study of Intertextuality,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 18 (2016): 159–170. Hopkin and Barney have rejected a strong parallel to Samuel of the Old Testament based on stylometric and narrative analysis. One challenge to comparing Samuel to the Biblical Samuel is that 1 and 2 Samuel may have been part of the Deuteronomistic History, a theoretical redacted source document for the books of Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings. Neal Rappleye and other Latter-day Saint scholars have argued that the Book of Mormon authors rejected the ideologies of these reformed texts. While the story of the biblical Samuel and David were certainly known to Book of Mormon authors, it is not surprising that the specific texts from 1 and 2 Samuel do not show up in this account. See Neal Rappleye, “The Deuteronomist Reforms and Lehi’s Family Dynamics: A Social Context for the Rebellions of Laman and Lemuel,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 16 (2015): 87–99.

- 2. The etymology of the name Samuel in Hebrew is “his name is God” or “name of God,” but Hannah employs the similar-sounding Hebrew phrase using the words shma and el as a paranomasia on Samuel’s name: “heard of God.” Ludwig Koehler and Walter Baumgartner, The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament (Leiden: Brill, 2001), 2:1554–1555; Francis Brown, S. R. Driver, and Charles A. Briggs, eds. and comps., A Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1978), 1028.

- 3. Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Benjamin Give Multiple Names for Jesus at the Coronation of his Son Mosiah? (Mosiah 3:8),” KnoWhy 536 (October 17, 2019); John W. Welch, “Textual Consistency,” in Reexploring the Book of Mormon: A Decade of New Research, ed. John W. Welch (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1992), 21–23. Samuel’s emphasis on believing on the name of Christ may be yet another possible wordplay on Samuel’s name, which means “name of God.”

- 4. Book of Mormon Central, “Why is the Lord's Hand ‘Stretched Out Still’? (2 Nephi 19:12),” KnoWhy 49 (March 8, 2016).

- 5. This insight comes from Hales Swift on The Interpreter Foundation radio show, “Audio Roundtable: Come, Follow Me Book of Mormon Lesson 35 (Helaman 13–16),” available online at interpreterfoundation.org.

- 6. Stretching forth one’s hand is a gesture of prophetic significance in both the Hebrew Bible and the Book of Mormon. The gesture often indicates prophetic speech and invokes the power of God (e.g. 1 Nephi 17:54; Mosiah 12:2; 3 Nephi 11:9). See David Calabro, “’Stretch Forth Thy Hand and Prophesy’: Hand Gestures in the Book of Mormon.” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 21, no. 1 (2012): 46–59; Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Abinadi Stretch Forth His Hand as He Prophesied? (Mosiah 16:1),” KnoWhy 94 (May 6, 2016). The stretched-out hand is also an attested gesture of speech in ancient America; see Kirk A. Magleby, “Mesoamerican Speech Gesture,” Book of Mormon Resources Blog (March 22, 2019), available online at http://bookofmormonresources.blogspot.com/2019/03/mesoamerican-speech-gesture.html.

- 7. Book of Mormon Central, “Why did Samuel Rely So Heavily on the Words of Past Prophets? (Helaman 14:1),” KnoWhy 185 (September 12, 2016); Hopkin and Hilton, “Samuel’s Reliance on Biblical Language,” 31–52; Barney, “Samuel the Lamanite, Christ, and Zenos,” 159–170; S. Kent Brown, “The Prophetic Laments of Samuel the Lamanite,” in From Jerusalem to Zarahemla: Literary and Historical Studies of the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 1998), 163–180; Donald W. Parry, “‘Thus Saith the Lord’: Prophetic Language in Samuel’s Speech,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 1, no. 1 (1992): 181–183.

- 8. Hopkin and Hilton, “Samuel’s Reliance on Biblical Language,” 44.

- 9. See John W. Welch, “Helaman 13–16,” John W. Welch Notes (Springville, UT: Book of Mormon Central, 2020).

KnoWhy Citation

Related KnoWhys

Subscribe

Get the latest updates on Book of Mormon topics and research for free