You are here

Why Is the Book of Mormon Called an “Abridgment”?

Title Page

The Know

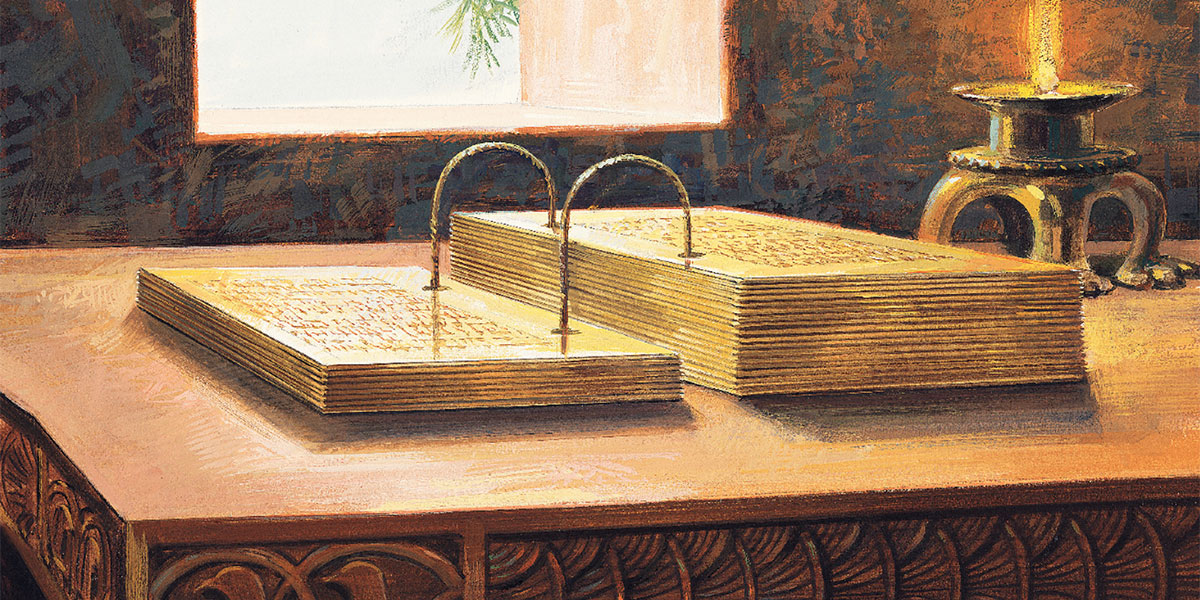

The Title Page of the Book of Mormon calls its text, as prepared by Mormon and Moroni, “an abridgment of the record of the people of Nephi, and also of the Lamanites.” It also refers to its account of Jaredite history as “an abridgment taken from the Book of Ether.” The prophet Nephi similarly referred to a portion of his writings as “an abridgment of the record of my father” (1 Nephi 1:17). An abridgment is a shortened version of a text, which means that the abridgments found in the Book of Mormon are only summaries of larger recorded histories.

The total amount of history that the Book of Mormon’s primary editors were working with must have been quite vast. Mormon and other prophets said they couldn’t include even a “hundredth part” of what had transpired among their people.1 Mormon also clues readers into the diverse nature of the underlying records that he was working with. At one point he explained that “there are many books and many records of every kind, and they have been kept chiefly by the Nephites” (Helaman 3:15). Some of these underlying records were summarized; others were quoted, in whole or in part, quite distinctively.

What were these different records? Anthropologist John L. Sorenson has conducted a careful analysis of the Book of Mormon’s source texts, comparing them to known record-keeping practices in ancient Mesoamerica. Based on his analysis, he proposed that the Book of Mormon’s underlying documents likely include the following categories:2

- Contemporary events

- Letters

- Victories and defeats in war

- Lives of rulers

- Adventures of individual heroes and villains

- Political histories

- Migration histories

- Information about ceremonial situations

- Prophecies

- Year counts and calendrical history

- Annals

- Tax or tribute lists

- Genealogies

- Divination

- Funerary texts

- Medical texts

- Lineage histories

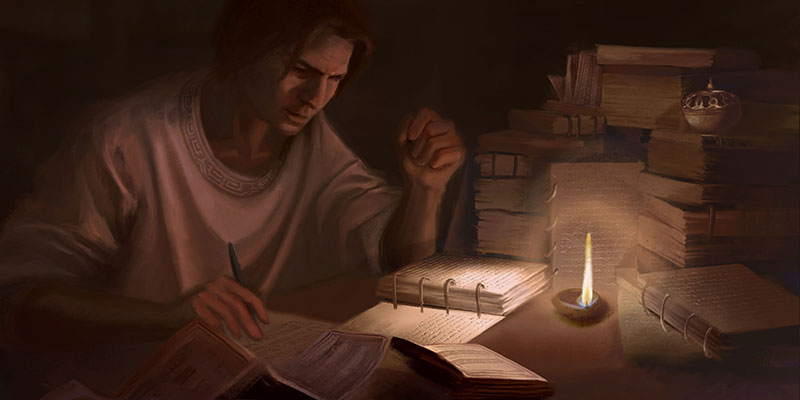

With admirable skill, Mormon and Moroni drew from these various historical records to create the final text—the abridged version of Nephite and Jaredite history as we know it.3 While the Book of Mormon may sometimes feel like a continuous story, the evidence of its being compiled from various sources is pervasive. Readers frequently encounter editorial commentary, discussions of source texts, adjustments in time or location, changes in genre, calculated variations in the amount of provided details, shifts between first and third person voices, telltale seams at points where one record was spliced into another, and other signs that the editors were weaving in and out of source materials.4

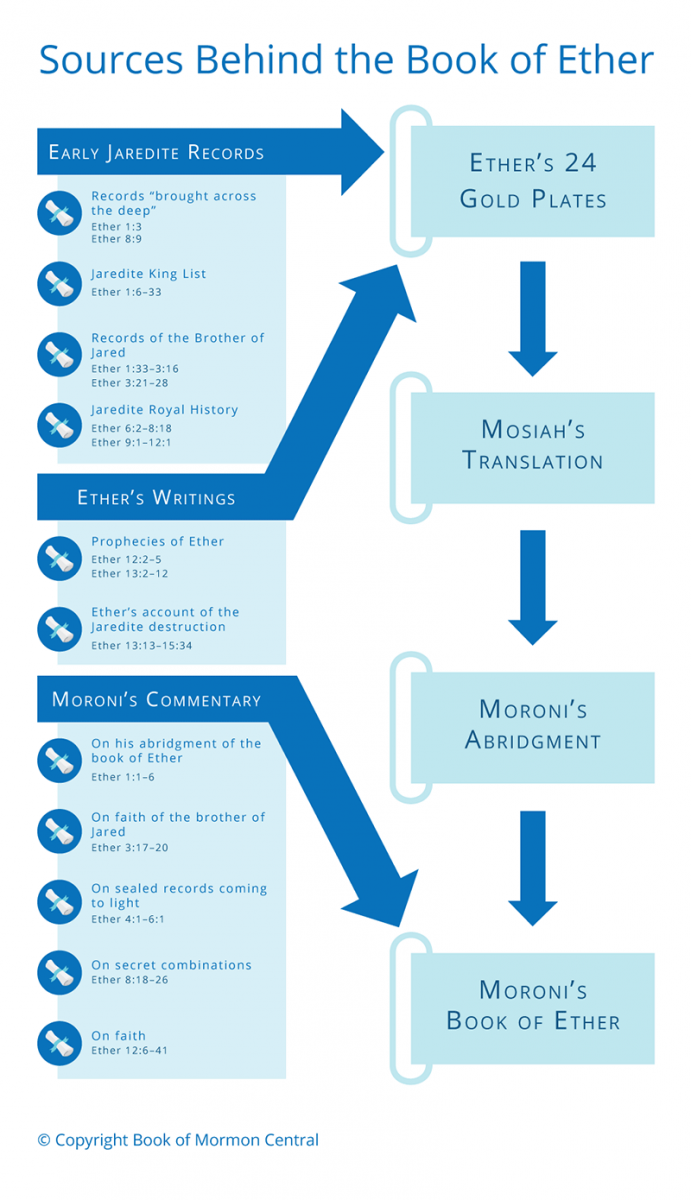

Sources Behind the Book of Ether in Charting the Book of Mormon.

Sometimes the sources are directly mentioned. For instance, in Helaman 2:13–14 Mormon said that the “book of Helaman” which he was currently drawing from was part of a larger history known as the “book of Nephi.” Moroni similarly explained, “I take mine account from the twenty and four plates which were found by the people of Limhi, which is called the Book of Ether” (Ether 1:2).5

On other occasions, identifying the underlying sources can be more complicated. For instance, readers may wonder how the specific details of Abinadi’s lengthy trial before King Noah and his priests (Mosiah 11–17) ever made it into Nephite history. As legal scholar John W. Welch has commented, “It is not entirely certain who spoke, reported, wrote, compiled, edited, or abridged the materials in Mosiah 11–17 as we now have them, or why these original reports or records were created. Yet it makes a difference who wrote this account and why.”6

After thorough analysis, Welch suggested that the record was likely derived from a combination of sources: Alma the Elder’s recollection of the trial, perhaps some of Alma’s followers who attended the trial after Alma was cast out, Limhi’s royal record of the trial, perhaps Ammon’s recollections from his time among Limhi’s people, and finally from Alma the Younger, who was “in a prime position to preserve, structure, and promote the story of Abinadi as it has come down to us today.”7

If Alma the Younger was truly the record’s primary architect before Mormon included it in his abridgment, that can influence how readers might interpret the record’s various themes. As Welch explained, the account of Abinadi’s trial meaningfully functions “as a prologue and rationalization for the ascendancy of Alma the Younger as the premier leader in the united land of Zarahemla.”8 Alma the Younger’s position as a chief judge might also explain why the details of the trial were discussed in such great depth—depth that Mormon, as a military commander, may not have included on his own.9

The Why

Words of Mormon by Normandy Poulter and the BYU Virtual Scriptures Group. Used with permission.

As these types of insights demonstrate, readers can benefit from frequently asking themselves why Mormon and Moroni included specific sources in the Book of Mormon’s final abridgment. Every narrative, sermon, prophecy, historical summary, letter, legal trial, military account, dialogue, or other type of source document was surely chosen for specific reasons.

Literary scholar Grant Hardy has noted that it is also “instructive to track how [Mormon] integrates documents into his narrative—where he places them, how he sets the scene for firsthand accounts or follows up on them later, whether they move forward or disrupt particular story lines, and whether they reinforce or call into question themes in the main narrative.”10 This type of attention to editorial choices and activities can lead to profound insights about the Book of Mormon’s source texts and the prophetic editors who drew upon them.

At the same time, such analysis can help strengthen a reader’s faith in the Book of Mormon’s historical authenticity.11 Hardy described the “Book of Mormon, with its multiple records, plates, writers, and editors, [as] anything but a naïve, straightforward narrative.”12

Its embedded documents are diverse, complex, and intricately fitted together for intelligent purposes. Simply trying to keep track of the mentioned source texts can be a chore for readers, yet the editors’ dutiful explanations of these records are consistent.13 In addition, subtle clues about undisclosed source documents, when pieced together through careful analysis, reveal realistic layers of textual strata that would be difficult for any author—especially one as uneducated and inexperienced as Joseph Smith—to fabricate.14

Readers can be confident, in light of such evidence, that the Book of Mormon is exactly what it claims to be—an abridgment of various ancient records. It condenses nearly 1,000 years of Nephite history and approximately 2,500 years of Jaredite history15 into a unified record that boldly and relentlessly testifies of Jesus Christ.16 Exploring how each of the Book of Mormon’s source texts individually contributes to the book’s primary message about Christ can be intellectually enlightening, spiritually satisfying, and ultimately faith promoting.

Further Reading

Anita Wells, “Bare Record: The Nephite Archivist, The Record of Records, and the Book of Mormon Provenance,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 24 (2017): 99–122.

John L. Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex: An Ancient American Book (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2013), 187–224.

John L. Sorenson, “Mormon’s Sources,” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 20, no. 2 (2011): 2–15.

Grant Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon: A Reader’s Guide (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2010), 121–151.

Brant A. Gardner, “Mormon’s Editorial Method and Meta-Message,” FARMS Review 21, no. 1 (2009): 87–98.

- 1. See Jacob 3:13; Words of Mormon 1:5; Helaman 3:14; 3 Nephi 5:8; 3 Nephi 26:6–7; Ether 15:33.

- 2. See John L. Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex: An Ancient American Book (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2013), 187–224. See also, John L. Sorenson, “The Book of Mormon as a Mesoamerican Record,” in Book of Mormon Authorship Revisited: The Evidence for Ancient Origins, ed. Noel B. Reynolds (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1997), 391–522, esp. 403–433.

- 3. For a discussion of Mormon’s sources, see John L. Sorenson, “Mormon’s Sources,” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 20, no. 2 (2011): 2–15. For a discussion of the sources behind the book of Ether, see John W. Welch, “Preliminary Comments on the Sources behind the Book of Ether,” FARMS Preliminary Reports (1986). Instances of scribes summarizing, combining, or anthologizing historical, religious, or legal texts can be observed in various ancient cultures and traditions.

- 4. On the remarkable presence of noticeable seams between sources behind the book of Ether, see John W. Welch and J. Gregory Welch, Charting the Book of Mormon: Visual Aids for Personal Study and Teaching (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1999), chart 15.

- 5. For a discussion of the pattern of naming records in the Book of Mormon, see Brant A. Gardner, “Mormon’s Editorial Method and Meta-Message,” FARMS Review 21, no. 1 (2009): 87–90. See also, Thomas W. Mackay, “Mormon as Editor: A Study in Colophons, Headers, and Source Indicators,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 2, no. 2 (1993): 90–109.

- 6. See John W. Welch, Legal Cases in the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: BYU Press and Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2008), 140.

- 7. Welch, Legal Cases, 143.

- 8. Welch, Legal Cases, 144.

- 9. See Welch, Legal Cases, 144: “Mormon may well have selected, abridged, edited, added to, or shaped parts of this section of the book of Mosiah as he compiled his set of plates, but it would not have served Mormon's purposes to create such a lengthy and detailed account of the trial itself. Only a lawyer, not a general, would care to give us all the legal information that we find in these chapters; and only a high priest still interested in the law of Moses would care to quote all of the Ten Commandments, let alone include the extensive midrashic exegesis of lsaiah 52 channeled through Isaiah 53 that is found in Mosiah 12–16.”

- 10. Grant Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon: A Reader’s Guide (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2010), 145.

- 11. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Is the Book of Mormon’s Historical Authenticity So Important? (Moroni 10:27),” KnoWhy 480 (October 30, 2018).

- 12. Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon, 121.

- 13. See Grant Hardy, “Book of Mormon Plates and Records,” Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 4 vols., ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (New York, NY: Macmillan, 1992), 195–201.

- 14. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Would God Choose an Uneducated Man to Translate the Book of Mormon? (2 Nephi 17:19),” KnoWhy 397 (January 9, 2018).

- 15. See John L. Sorenson, “The Years of the Jaredites” FARMS Preliminary Reports (1969).

- 16. See Book of Mormon Central, “What Was Mormon’s Purpose in Writing the Book of Mormon? (Mormon 5:14),” KnoWhy 230 (November 14, 2015); Book of Mormon Central, “Why Is the Book of Mormon ‘Another Testament of Jesus Christ’? (2 Nephi 3:12),” KnoWhy 949 (December 18, 2018).

KnoWhy Citation

Related KnoWhys

Subscribe

Get the latest updates on Book of Mormon topics and research for free