You are here

How Was the Transfiguration of Jesus and the Three Nephites a Temple-Like Experience?

3 Nephi 28:15

The Know

The synoptic gospels record that Jesus was transfigured in the presence of His three apostles Peter, James, and John (Matthew 17:1–13; Mark 9:2–10; Luke 9:28–36).1 These accounts agree with each other on the general details of what transpired at the transfiguration:

- It took place on a high mountain

- It included Peter, James, and John as witnesses

- Jesus’ countenance and clothing shown white

- Moses and Elijah (Elias) appeared

- Peter offered to build “tabernacles” for Jesus, Moses, and Elijah (Elias)

- A cloud overshadowed the participants and a voice was heard declaring, “This is my beloved Son: hear him.”

- The disciples were overcome in fear or awe at what they heard and witnessed

- The disciples were sworn to secrecy about what happened

The individual gospel accounts offer slightly differing details that add to this episode. For instance, the Gospel of Matthew reports that the voice out of heaven (God the Father) declared not only that Jesus was His beloved son, but that He was “well pleased” with Him (Matthew 17:5).2 Luke reports that sleep came upon the three disciples during part of the event (perhaps because of the exertion that sometimes accompanies divine visitations or manifestations) and that the three awoke to behold Jesus’s glory and the two heavenly beings who stood with Him (Luke 9:32).3 Only Matthew says that Jesus touched them and bade them “arise” (Matthew 17:7). The Gospels of Matthew and Mark both record that it was Jesus himself who swore the disciples to secrecy about what transpired on the occasion (Matthew 17:9; Mark 9:9), a detail absent in Luke’s report, although Mark and also Luke affirm that they told no one the “things . . . they had seen” (Mark 9:9-10; Luke 9:36, see also 9:21).

Restoration scripture offers insight into this episode. A revelation received by the Prophet Joseph Smith in 1831 clarified that we have not yet received the full account of what occurred at the transfiguration, but that it apparently included a vision granted to the disciples of the final celestialization of the earth (Doctrine and Covenants 63:20–21).

A textual variant in the Joseph Smith Translation of Mark 9 also raises questions about who it was precisely that appeared to Jesus at the transfiguration:

|

JST Mark 9:3 |

|

|---|---|

|

And there appeared unto them Elias with Moses: and they were talking with Jesus.

|

And there appeared unto them Elias with Moses, or in other words, John the Baptist and Moses; and they were talking with Jesus |

The name Elias as it appears in the Greek New Testament is simply the Greek rendering of the name Elijah. However, the JST reading of this verse in Mark, together with the explanations in Matthew 17:13, indicate that “the disciples understood that [Jesus] spake unto them of John the Baptist and also of another who should come and restore all things.” It may be that John the Baptist and Moses were the ones at the Transfiguration rather than Elijah and Moses. In addition, the name Elias can refer to several messengers who are called to act in the capacity of an Elias, a forerunner or preparer. Perhaps, then, John the Baptist (Elias) came to prepare Jesus to be received into the presence of the translated prophets Moses and Elijah.4 This reading would be in harmony with how Elias is used broadly as a type for “forerunner” or for one who comes as a restorer in Joseph Smith’s revelations (and in the New Testament and even other nineteenth century Christian literature, for that matter).5

Mosaic of the Transfiguration of Christ above the altar in the chapel at St. Catherine's monastery in the Sinai. Photo by Laura Paskett.

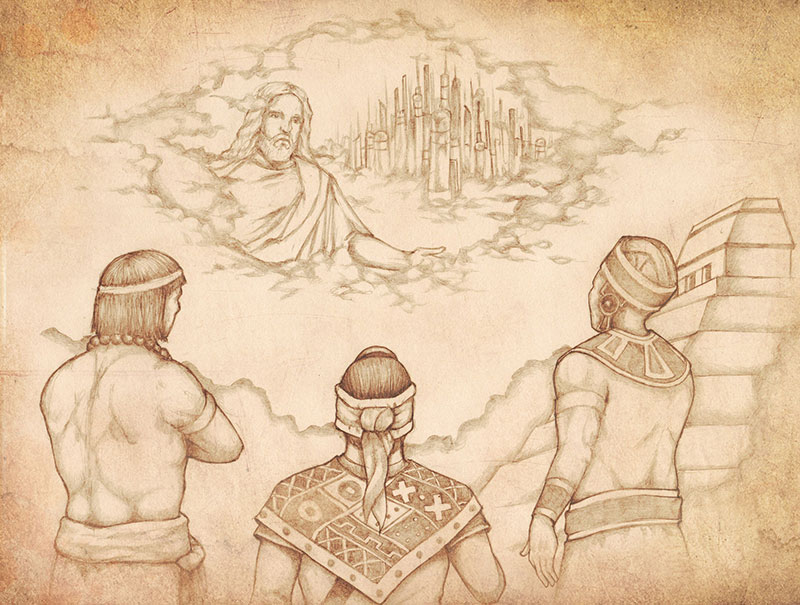

Another occasion of “transfiguration” is recorded in the Book of Mormon (3 Nephi 28:15, 17). Here, the resurrected Lord was not the one transfigured. He had already been glorified. But three of His chosen disciples in the New World experienced a similar transfiguring event, including a greater fullness of blessings than circumstances had allowed Peter, James, and John to receive in the middle of Jesus’s Galilean ministry.

As recorded in 3 Nephi, after his previous appearances among the righteous people at the temple in Bountiful, the resurrected Jesus visited privately with His twelve New World apostles and offered them the opportunity to ask something of Him after He had returned back to the Father (3 Nephi 28:1). Three of those Nephite disciples wanted to ask, but “durst not speak unto [Jesus] the thing which they desired” (3 Nephi 28:5). Jesus, however, knew what they desired: “Behold, I know your thoughts, and ye have desired the thing which John, my beloved, who was with me in my ministry, before that I was lifted up by the Jews, desired of me” (v. 6). In other words, Jesus knew that these three disciples desired to “tarry until [Jesus] come in [His] glory,” and thereby be able to “prophesy before nations, kindreds, tongues and people” (D&C 7:3).

In response to this righteous desire, Jesus promised the three Nephite disciples:

- that they would never taste death, which Christ had by then overcome (3 Nephi 28:7).

- that they would “live to behold all the doings of the Father unto the children of men” (v. 7).

- that they would “never endure the pains of death; but when [Jesus] shall come in [his] glory [they] shall be changed in the twinkling of an eye from mortality to immortality” (v. 8).

- that they would “not have pain while [they] shall dwell in the flesh, neither sorrow save it be for the sins of the world” (v. 9).

- that they would have a “fullness of joy” and “sit down in the kingdom of [the] Father” (v. 10).

- that they should be one with Jesus and the Father (v. 10).

These remarkable promises of divine transformation were then followed by a glorious vision. In this vision, “the heavens were opened, and they [the three Nephite disciples] were caught up into heaven, and saw and heard unspeakable things. And it was forbidden them that they should utter; neither was it given unto them power that they could utter the things which they saw and heard” (3 Nephi 28:13–14).

The text in 3 Nephi goes on to explicitly call this event a “transfiguration” twice (3 Nephi 28:15, 17), and comments that the three Nephite disciples “were changed from this body of flesh into an immortal state, that they could behold the things of God” (v. 15). Although he wanted to write more about this incident, including the names of the three Nephite disciples, Mormon was forbidden to do so (v. 25). What he was allowed to say was that “[the three Nephite disciples] are as the angels of God, and if they shall pray unto the Father in the name of Jesus they can show themselves unto whatsoever man it seemeth them good” (v. 30).

The Why

The shared elements in these transfiguring events reported in the synoptic gospels and in 3 Nephi invite the question, Can a wider pattern of sacred temple features be discerned as standing behind these two encounters with the divine? And why would the holy temple of ancient Israel be a point of common origin linking them? Because the law of Moses and the temple in Jerusalem were foundational for both the Jews in Galilee and the Nephites in Bountiful, one should not be surprised to find Moses and the holy temple of ancient Israel as a precedent in both of these spheres.

Indeed, the New Testament accounts of Jesus’ transfiguration share several elements with Moses’ encounter with God on the mount (as well as other Jewish motifs).6 The most obvious of these are the high mountain setting, Jesus being accompanied on the mountain by three companions, a cloud overshadowing the scene, a divine voice coming out of the cloud, and Jesus’ changed countenance and white clothing.

|

Jesus (Matthew 17:1–13; Mark 9:2–10; Luke 9:28–36) |

|

|---|---|

|

Moses ascends a high mountain (Exodus 19:20). |

Jesus ascends a high mountain. |

|

Moses ascends the mount with three companions (Aaron, Nadab, Abihu) and seventy elders (Exodus 24:1, 9).

|

Jesus is accompanied by Peter, James, and John. |

|

God’s glory and appearance is concealed by a cloud (Exodus 24:15).

|

A cloud overshadows the scene. |

|

A voice speaks “out of the midst of the cloud” (Ex. 24:16).

|

A voice speaks out of the cloud. |

|

Moses is transfigured and his skin shines when he has concluded speaking with God (Exodus 34:29). |

Jesus is transfigured; His clothes become dazzling white and his countenance changes. |

|

The children of Israel are “afraid to come nigh” unto Moses after his descent from the mountain (Exodus 34:30). |

The disciples are afraid during the event. |

The fact that Moses himself was one of the personages who appeared to Jesus and the disciples during the Transfiguration leaves little doubt that the gospel writers wanted their readers to thematically link the supernal experience of the Old Testament lawgiver and prophet Moses with that of Jesus.7

Additionally, the element of Peter wanting to build “tabernacles” for Jesus, Moses, and Elias/Elijah further associates this episode with the temple. The Greek word used to describe the “tabernacles” Peter wanted to build (skēnē) is the same word used in the ancient Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible for the Tabernacle of Moses. A few scholars have even suggested parallels between the Transfiguration and the Jewish Feast of Tabernacles.8

Christians through the centuries have also recognized the significance that the transfiguration of Jesus held for the doctrine of theosis or deification (the teaching that Christ’s disciples had the potential to become like God).9 Several elements in the Transfiguration narrative were likened to the glorious transformation of believers at the time of Jesus’ return in early Christian literature.10 As one scholar noted, “This sense of transformation, theosis, can be detected in [the] account of the transfiguration.”11

Likewise, temple and deification themes are also unmistakable in the transfiguration of the three Nephite disciples, such as the three Nephites being promised that they would enjoy a “fullness of joy” and “sit down in the kingdom of [the] Father” where they would be one with Jesus and the Father (3 Nephi 28:10). The detail that the three Nephite disciples were “caught up into heaven, and saw and heard unspeakable things”—things that were “forbidden them that they should utter”—additionally links this passage to the temple and the process of becoming like God.12

Although we can only glimpse a small part of the power and expansiveness of each of these transfiguration experiences of Moses, Jesus, and the Three Nephites, we can begin to absorb more of their spirits of holy promise into our souls as we embrace and interlace them all.

Little wonder that the Savior, Moses, Elijah, and another Elias (John the Baptist?) would choose to appear to Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery in the Kirtland Temple when the time came to restore important priesthood keys (D&C 110). These keys would enable the Prophet to restore the ordinances of the temple, gather the house of Israel, and make available again the blessings of Abraham, thus providing God’s children the opportunity to return back to their Father’s presence and partake of eternal life, exaltation, and a fullness of joy (D&C 124:37–44; 132:7–24).13

This KnoWhy was made possible by the generous support of the Dow and Lynne Wilson Family.

Further Reading

Robert L. Millet, “Make Your Calling and Election Sure,” in The Ministry of Peter, the Chief Apostle, ed. Frank F. Judd Jr., Eric D. Huntsman, and Shon D. Hopkin (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2014), 267–282.

Kenneth L. Alford, “I Will Send You Elijah the Prophet,” in You Shall Have My Word: Exploring the Text of the Doctrine and Covenants, ed. Scott C. Esplin, Richard O. Cowan, and Rachel Cope (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2012), 34–349.

Clyde J. Williams, “The Three Nephites and the Doctrine of Translation,” in 3 Nephi 9–30, This Is My Gospel, Book of Mormon Symposium Series, Volume 8, ed. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate, Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 1993), 237–251.

- 1. Matthew and Mark report that the transfiguration took place near Caesarea Philippi not long after Peter testified of Jesus being the Christ and receiving the sealing power (Matthew 16:13–20; Mark 8:27–33). Luke does not give any hints as to the geographical location of the transfiguration but does report that it took place shortly after the same incident (Luke 9:18–22).

- 2. The other instances in recorded scripture where the Father declared Jesus’ divine sonship include the baptism of Jesus (Matthew 3:17; Mark 1:11; Luke 3:22), Jesus’ appearance to the Nephites (3 Nephi 11:7), and Joseph Smith’s First Vision (Joseph Smith–––History 1:17). The slight variations between these testimonies are noteworthy. At the baptism of Jesus, the voice of the Father declared that he was “well pleased” with His Son. When the Savior appeared to the Nephites, the Father testified that Jesus was the one “in whom I [the Father] have glorified my name” through His Son’s accomplishment of the Atonement and Resurrection. He also commanded the Nephites to hear His Son. Likewise, when the Father and the Son appeared to the boy Joseph, the Father commanded Joseph to hear the words of His Son, a parallel with the instruction given at the Transfiguration and in 3 Nephi. These variations would seem to indicate that the content of Father’s testimony of His Son was contingent on the setting and the audience receiving the testimony.

- 3. Compare Joseph Smith’s 1838 First Vision account where he recorded, “When I came to myself again, I found myself lying on my back, looking up into heaven. When the light had departed, I had no strength; but soon recovering in some degree, I went home” (Joseph Smith–––History 1:20).

- 4. It is interesting to note that Joseph Smith did not make the same change to the verses in Matthew and Luke identifying Elias (Elijah) and Moses as those who conversed with Jesus.

- 5. See the discussion in Robert Boylan, “‘Elias’ as a ‘forerunner’ in LDS Scripture,” Scriptural Mormonism blog (August 10, 2014), online at www.scripturalmormonism.blogspot.com. See also the comment in Grant Underwood, “Joseph Smith and the King James Bible,” in The King James Bible and the Restoration, ed. Kent P. Jackson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2011), 223–224. “Although Joseph Smith had only limited familiarity with New Testament Greek, he occasionally came to new insights with respect to certain Greek words in the Bible. ‘Elias,’ for instance, is the Greek transliteration of the Hebrew name ‘Elijah’ or ‘Eliyahu.’ Yet, because the King James translators consistently rendered or transliterated names into English directly from the language with which they were working, ‘Elijah’ never appears in the New Testament. Even in passages such as James 5:17 or Romans 11:2, where the accompanying text refers unmistakably to the Old Testament prophet Elijah, the King James translators used the transliteration ‘Elias.’ Contemplation of the somewhat ambiguous Elias references in the New Testament led the Prophet to the novel realization that Elias was more than a single person, that Elias was actually a name-title for different individuals who, like John the Baptist, functioned ‘in the spirit and power of Elias . . . to make ready a people prepared for the Lord’ (Luke 1:17) or who assisted in the ‘restoration of all things’ (D&C 27:6). In addition to John the Baptist, Joseph Smith learned that the angel Gabriel who visited Zacharias was an Elias (see D&C 27:7) and that John the Revelator’s end-time mission to assist in gathering the tribes of Israel qualified him to be a latter-day Elias as well (see D&C 77:14). Moreover, prior to Elijah’s visit to the Prophet Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery in the Kirtland Temple, yet another Elias appeared ‘and committed . . . the gospel of Abraham’ (D&C 110:12).”

- 6. Herbert W. Basser, “The Jewish Roots of the Transfiguration,” Bible Review, June 1998, 30–35.

- 7. See additionally Scott Connell, “Implications for Worship from the Mount of Transfiguration,” Artistic Theologian 4 (2016): esp. 33–39. Armand Puig Tàrrech, “The Glory on the Mountain: The Episode of the Transfiguration of Jesus,” New Testament Studies 58 (2012):154–156, stresses that the parallels with Moses should not be overplayed, but nevertheless recognizes them. For an extended discussion of the literary and theological themes shared in the Transfiguration story with Old Testament scripture and other Jewish writings, see A. D. A. Moses, Matthew’s Transfiguration Story and Jewish-Christian Controversy (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1996), esp. 50–113.

- 8. Margaret Barker, Temple Mysticism: An Introduction (London: SPCK, 2011), 58; Tàrrech, “The Glory on the Mountain,” 156–158.

- 9. See for instance the discussion in Norman Russell, The Doctrine of Deification in the Greek Patristic Tradition (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2004), 200, 259, 292–293, 295, 311. For a Latter-day Saint perspective on this teaching, see “Becoming Like God,” Gospel Topics Essay, online at www.lds.org.

- 10. Simon S. Lee, Jesus’ Transfiguration and the Believers’ Transformation: A Study of the Transfiguration and Its Development in Early Christian Writings (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2009), 213–214. See also the discussion in Crispin H. T. Fletcher-Louis, Luke-Acts: Angels, Christology, and Soteriology (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1997), 38–50, 222–224.

- 11. Margaret Barker, Temple Themes in Christian Worship (London: T&T Clark, 2007), 114.

- 12. Clyde J. Williams, “The Three Nephites and the Doctrine of Translation,” in 3 Nephi 9–30, This Is My Gospel, Book of Mormon Symposium Series, Volume 8, ed. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate, Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 1993), 237–251.

- 13. In a discourse delivered sometime between 26 June and 4 August 1839, the Prophet taught, “The priesthood is everlasting. The Savior, Moses, and Elias gave the keys to Peter, James, and John on the mount when they were transfigured before him. The priesthood is everlasting; without beginning of days or end of years, without father, mother, etc.” Discourse, between circa 26 June and circa 4 August 1839–A, as Reported by Willard Richards, online at www.josephsmithpapers.org, punctuation and spelling standardized. A clear line can thus be drawn from the keys given to Peter, James, and John at the Transfiguration with the keys restored to Joseph Smith in the Kirtland Temple.

KnoWhy Citation

Related KnoWhys

Subscribe

Get the latest updates on Book of Mormon topics and research for free