You are here

How Did Enos Liken the Scriptures to His Own Life?

Enos 1:27

The Know

Nephi said that he “did liken all scriptures unto us, that it might be for our profit and learning” (1 Nephi 19:23).1 The Book of Mormon offers many ways that the scriptures can be applied to our own lives. The story of the prophet Enos demonstrates some of the ways this can be done.2 Certain phrases in the book of Enos show how Enos applied the scriptures directly to his own life.

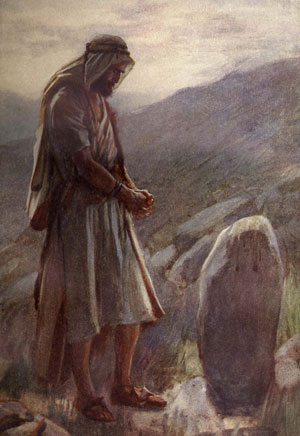

John A. Tvedtnes and Matthew Roper argued that Enos alluded to the man his father may have been named after: Jacob.3 Immediately after calling his father, Jacob, a “just man” (Enos 1:1), Enos wrote of “the wrestle which I had before God, before I received a remission of my sins” (Enos 1:2). The two clues to the allusion are the name Jacob in both stories and that just as Enos wrestled before God, so too did the patriarch Jacob wrestle with “a man” all night long (Genesis 32:24–28).

One significant similarity between Enos and Jacob is that “when Enos wrote about his wrestling, he evidently was referring not only to his struggle to overcome sin but also to his prayers for both the Lamanites and the Nephites (Enos 1:9–18).”4 Tvedtnes and Roper noted that, just as Enos prayed for the Lamanites, his brothers, during his wrestle with God, Jacob may also have been praying for his brother Esau during his wrestle.

At the time of this encounter, Jacob was coming home after two decades in Syria. Esau had wanted to kill him when he left (Genesis 27:41–45), but now Jacob was earnestly praying that God would preserve him from his brother (Genesis 32:9–12). In the same way, Enos devoutly prayed that God would preserve the records from his “brothers,” the Lamanites (Enos 1:13), who also had murderous intent toward the Nephites.

Even the phrase, “I will tell you of the wrestle which I had before God” is significant (Enos 1:2). In Hebrew, the words before God would literally mean “to the face of God.” When the Patriarch Jacob realized that the “man” he was wrestling with was divine, he called the place Peniel, which comes from the same Hebrew phrase, meaning “the face of God.”5 In addition, the Hebrew word for wrestle, which one could read as jaboc, sounds similar to the name Jacob, just with the “b” and “c” inverted, a clear playfulness with words so typically practiced by ancient Israelite writers.6

According to linguistic scholar Matthew Bowen, this pun “reminds [Enos’s] audience that his father, the ‘just man’ mentioned in Enos 1:1, is named for their ancestor Jacob, who also had a ‘wrestle.’ Patriarch Jacob’s transformative experience will be, in some measure, Enos the son of Jacob’s experience.”7 When Enos finished “wrestling,” he was “blessed” (Enos 1:5), just as Jacob was likewise blessed directly by God (Genesis 32:26). 8

After his experience “wrestling” and beseeching God, Jacob was finally reconciled with his brother, Esau (Genesis 33:3–4).9 This detail helps to explain part of the point of Enos’s account. Just as Jacob was reconciled to his brother Esau after wrestling with God, Enos was promised that his people would be reconciled to their brethren, the Lamanites, after his wrestle with God (Enos 1:12–17).10

In addition to allusions in the Genesis story, it seems that Enos also applied a portion of the book of Job directly to himself. Job 33:26, begins: “he shall pray unto God, and he will be favourable unto him.” This is a fitting summary of the book of Enos. It is followed by a phrase that Enos seems to have copied almost verbatim: “and he shall see his face with joy: for he will render unto man his righteousness” (Job 33:26). As the conclusion to his book, Enos also stated, referring to God, “Then shall I see his face with pleasure, and he will say unto me: Come unto me, ye blessed, there is a place prepared for you in the mansions of my Father” (Enos 1:27).

Enos may have included this verse because he saw himself in it, literally. The Hebrew word for “man” used in Job 33:26 is enosh,11 likely the same Hebrew word from which Enos derives.12 Thus, Enos may have read this verse as “and he shall see his face with joy, for he will render unto Enos his righteousness.”13 This may have prompted Enos to end his book with this quotation. It may also have prompted him to describe exactly what God would render to him because of his righteousness: a place in the mansions of his Father.14

The Why

These examples show how Enos “likened the scriptures” to himself. Enos seems to have read his scriptures carefully and then worked hard to apply them directly to his own life. Like Jacob of old, Enos begged God mightily to grant him the desired blessing. Enos may even have “put his own name” into a verse, as people sometimes wisely do today. This helps to show modern readers that they can apply the scriptures directly to themselves in a very specific way.

However, it seems that Enos also applied the scriptures to himself in a much broader way as well. In addition to looking at a specific, isolated verse and applying it to himself, as in the example from Job, Enos also looked at the broader similarities between his own experiences and Jacob’s experiences.

He then saw how these broad similarities could be applied in his own life. In doing this, he stumbled upon something profound. Just as Jacob was reconciled with his brother who had tried to kill him, so too would the Nephites, through their records, be reconciled to the descendants of the Lamanites, their brethren who had tried to kill them. Besides helping the modern reader understand Enos better, this also demonstrates two ways to “liken” the scriptures. By applying scriptures in their broader context, as well as in isolation, modern readers can get more out of the scriptures to help them in their daily lives.

Applying scriptures in their context, like Enos does, is crucial to understanding the scriptures:

The context is a means to understand the content of the scriptures. It provides background information that clarifies and brings a depth of understanding to the stories, teachings, doctrines, and principles in the scriptural text... To understand their writings, teachers and students should mentally “step into their world” as much as possible to see things as the writer saw them.15

When readers apply these scriptures in context as well as in isolation, it can help them to see and enact the full richness of the scriptures in their own lives.

Further Reading

Matthew Bowen, “‘And There Wrestled a Man with Him’ (Genesis 32:24): Enos’s Adaptations of the Onomastic Wordplay of Genesis,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 10 (2014): 153.

Matthew L. Bowen, “Wordplay on the Name 'Enos',” Insights: A Window on the Ancient World 26, no. 3 (2006): 2.

John A. Tvedtnes, “Jacob and Enos: Wrestling before God,” Insights: A Window on the Ancient World 21, no. 5 (2001): 2.

- 1. See Book of Mormon Central, “How Might Isaiah 48-49 be “Likened” to Lehi's Family? (1 Nephi 19:23),” KnoWhy 23 (February 1, 2016).

- 2. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Jesus Quote All of Isaiah 54 (3 Nephi 22:5),” KnoWhy 216 (October 25, 2016).

- 3. John A. Tvedtnes and Matthew Roper, “Jacob and Enos: Wrestling before God,” Insights: A Window on the Ancient World 21, no. 5 (2001): 2.

- 4. Tvedtnes and Roper, “Wrestling before God,” 2.

- 5. Tvedtnes and Roper, “Wrestling before God,” 2.

- 6. Matthew Bowen, “‘And There Wrestled a Man with Him’ (Genesis 32:24): Enos’s Adaptations of the Onomastic Wordplay of Genesis,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 10 (2014): 153.

- 7. Bowen, “‘And there Wrestled a Man,” 153.

- 8. Bowen, “‘And there Wrestled a Man,” 154.

- 9. Bowen, “‘And there Wrestled a Man,” 155.

- 10. Bowen, “‘And there Wrestled a Man,” 157.

- 11. Francis Brown, S. R. Driver, and Charles Briggs, A Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament (Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1951), 60. In the Hebrew alphabet of Lehi’s day, the same letter was used to represent sh and s. The difference between these two was fluid and often varied by dialect. Note, for example, the inability of northern Israelites like Lehi’s ancestors to pronounce the sh sound (Judges 12:6). See William M. Schniedewind, A Social History of Hebrew: Its Origins Through the Rabbinic Period (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013), 13–14.

- 12. See Matthew Bowen, “Wordplay on the Name ‘Enos’,” Insights: A Window on the Ancient World 26, no. 3 (2006): 2; “Enos,” Book of Mormon Onomasticon, ed. Paul Y. Hoskisson.

- 13. Personal conversation, Carli Anderson, September 2011.

- 14. That subtle wordplay like this is a possibility is supported by Enos’s introduction: “Behold, it came to pass that I, Enos, knowing my father that he was a just man.” This is likely another play on the similarity between his name and the word for “man,“ not unlike Nephi’s wordplay in 1 Nephi 1:1, ”I, Nephi [goodly], having been born of goodly parents.” See Bowen, “Wordplay on the Name 'Enos',” 2.

- 15. Gospel Teaching and Learning: A Handbook for Teachers and Leaders in Seminaries and Institutes of Religion (Salt Lake City, UT: Intellectual Reserve, 2012), 24.

KnoWhy Citation

Related KnoWhys

Subscribe

Get the latest updates on Book of Mormon topics and research for free