You are here

When Did Cement Become Common in Ancient America?

Helaman 3:7

The Know

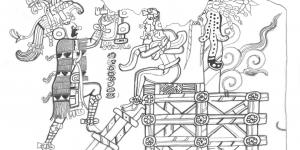

In the mid-first century BC, Mormon reports that some Nephite dissenters “did travel to an exceedingly great distance” into “the land northward,” where they found “large bodies of water and many rivers” (Helaman 3:3–4). There was “little timber” in the region, and these people “became exceedingly expert in the working of cement,” and thus built “houses of cement,” and even built “many cities, both of wood and of cement” (vv. 7, 9, 11).

Ancient American cement was made using limestone, and has, thus far, only been found in Mesoamerica.1 While some people were aware of pre-Columbian American cement in the early 19th century,2 its origins, history, and development remained obscure well into the 20th century.

In 1970, David S. Hyman was “not able to uncover clues relative to the origins of American cement manufacturing.”3 The earliest samples he had found dated to the first century AD but were so “technically well advanced” that Hyman was convinced there must have been earlier, less developed forms.4

Since that time, earlier precedents have indeed been found. In a 1991 report, Matthew G. Wells documented that a “limey whitewash,” which was “not structural” but “is believed to be a precursor to later structural developments,” was in use as early as the ninth century BC.5 During the Middle Preclassic period (ca. 800–300 BC), “the Maya of the lowlands had discovered … that if limestone fragments were burnt, and the resulting powder mixed with water, a white plaster of great durability was created.”6

According to Mayan experts Michael D. Coe and Stephen Houston, it was not until the Late Preclassic period (300 BC–AD 250) that the Maya “quickly realized the structural value of a concrete-like fill made from limestone rubble” and lime-rich mud.7 This led to “an explosion of activity around 100 BC.”8 One area where cement was used extensively was the city of Teotihuacán in central Mexico, which some Book of Mormon scholars consider to be in the land northward.9

These discoveries place the development and expansion of lime cement in Mesoamerica for structural building construction very close to the same period that the cement mentioned in the Book of Mormon becomes widespread in the northern lands.

The Why

Despite the fact that pre-Columbian cement had been known to some in the early 19th century, the Book of Mormon was criticized for this point as recently as the early 20th century. In 1929, Heber J. Grant related a story from his youth where a fellow with a doctorate “ridiculed [him] for believing in the Book of Mormon.” This was because it mentioned that “people had built their homes out of cement and that they were very skillful in the use of cement.”

This well-educated young man went on to declare, “There had never been found and never would be found, a house built of cement by the ancient inhabitants of this country, because the people in that early age knew nothing about cement.”

According to President Grant, he responded by bearing impassioned testimony of the Book of Mormon:

That does not affect my faith one particle. I read the Book of Mormon prayerfully and supplicated God for a testimony in my heart and soul of the divinity of it, and I have accepted it and believe it with all my heart. … If my children do not find cement houses, I expect that my grandchildren will.

His antagonist responded with more ridicule. “Well what is the good of talking to a fool like that.”10 Grant did not have to wait for future generations to validate the Book of Mormon on this point. Despite being well-educated, his friendly critic was misinformed—cement had already been found in pre-Columbian America. Still, as in so many other instances, as more is learned about cement in ancient America, the correlation with the Book of Mormon gets stronger.

John L. Sorenson observed, “The first-century-BC appearance of cement in the Book of Mormon agrees strikingly with the archaeology of central Mexico.”11 Both Sorenson and John W. Welch remarked, “No one in the nineteenth century could have known that cement, in fact, was extensively used in Mesoamerica beginning at about this time, the middle of the first century BC.”12 And it is more than the mere mention of cement. As Welch put it, “The dating by archaeologists of this technological advance to the precise time mentioned in the book of Helaman seems far from knowable to anyone in the world in 1829.”13

While other examples of alleged anachronisms have revealed the value in being patient and waiting for new light from archaeology,14 this example teaches another kind of lesson: sometimes, even well-educated and well-intended people can be wrong (cf. 2 Nephi 9:28–29).

Rather than panicking at overconfident dismissals or jumping to presupposed outcomes, it is always wiser to continue to investigate the facts to the best of one’s ability. In some cases, further time and patience may be necessary to bring additional clarity and understanding, but in other cases—as with cement—the concrete evidence that people can confidently build upon is gratefully already available.15

Further Reading

Matthew Roper, “Exceedingly Expert in the Working of Cement (Howlers #9),” Ether’s Cave: A Place for Book of Mormon Research, July 1, 2013, online at http://etherscave.blogspot.com/2013/07/exceedingly-expert-in-working-of-...

John L. Sorenson, “How Could Joseph Smith Write So Accurately about Ancient American Civilization?,” in Echoes and Evidences of the Book of Mormon, ed. Donald W. Parry, Daniel C. Peterson, and John W. Welch (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2002), 287–288.

Matthew G. Wells and John W. Welch, “Concrete Evidence for the Book of Mormon,” in Reexploring the Book of Mormon: A Decade of New Research, ed. John W. Welch (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1992), 212–214.

- 1. See Matthew G. Wells and John W. Welch, “Concrete Evidence for the Book of Mormon,” in Reexploring the Book of Mormon: A Decade of New Research, ed. John W. Welch (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1992), 212–214; John L. Sorenson, “How Could Joseph Smith Write So Accurately about Ancient American Civilization?,” in Echoes and Evidences of the Book of Mormon, ed. Donald W. Parry, Daniel C. Peterson, and John W. Welch (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2002), 287–288; John W. Welch, “A Steady Stream of Significant Recognitions,” in Echoes and Evidences, 372–374.

- 2. In a letter written to President Heber J. Grant, dated March 1, 1932, B. H. Roberts shared some sources from the late 18th and early 19th century which mentioned the use of cement in the construction of buildings by pre-Columbian Native Americans. A copy of this letter is in Book of Mormon Central’s possession.

- 3. David S. Hyman, Precolumbian Cements: A Study of the Calcareous Cements in Prehispanic Mesoamerican Building Construction (PhD dissertation, John Hopkins University, 1970), ii.

- 4. Hyman, Precolumbian Cements, ii; sec. 6, p. 15.

- 5. Matthew G. Wells, “Cement in Ancient Mesoamerica: A Survey,” unpublished manuscript, October 1991 (updated February 1998), p. 2. A copy of this report is in Book of Mormon Central’s possession.

- 6. Michael D. Coe and Stephen Houston, The Maya, 9th edition (London, UK: Thames and Hudson, 2015), 81.

- 7. Coe and Houston, The Maya, 81. The full quote mentions “rubble and marl,” which is a “lime-rich mud or mudstone which contains variable amounts of clays and silt.” See Wikipedia, s.v., “Marl,” online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marl (accessed August 9, 2016).

- 8. Coe and Houston, The Maya, 81.

- 9. Rene Millon and James A. Bennyhoff, “A Long Architectural Sequence at Teotihuacán,” American Antiquity 26, no. 4 (1961): 516–523; Rebecca Sload, “Radiocarbon Dating of Teotihucán Mapping Project TE28,” FAMSI, 2007, online at famsi.org, each mention finding charcoal underneath concrete structures which was radiocarbon dated to ca. 50 BC–AD 110, although both dated the use of concrete at their respective sites to later phases of development. For Latter-day Saint discussion connecting Teotihuacán to the land northward, see John L. Sorenson, An Ancient American Setting for the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1985), 266–267; Joseph L. Allen and Blake J. Allen, Exploring the Lands of the Book of Mormon, revised edition (American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 2011), 193–213; Brant A. Gardner, Traditions of the Fathers (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2015), 327–337.

- 10. This story is related in Heber J. Grant, Conference Report, April 1929, p. 129; cited in Matthew Roper, “Exceedingly Expert in the Working of Cement (Howlers #9),” Ether’s Cave: A Place for Book of Mormon Research, July 1, 2013, online at http://etherscave.blogspot.com/2013/07/exceedingly-expert-in-working-of-... (accessed August 8, 2016). Roberts to Grant, March 1, 1932, identified the antagonist as a Mr. Morgan, brother of John Morgan.

- 11. John L. Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex: An Ancient American Book (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2013), 322.

- 12. Sorenson, “How Could Joseph Smith Write So Accurately,” 287. Welch, “A Steady Stream,” 372–373, differs only slightly in wording: “No one in the nineteenth century could have known that cement, in fact, was extensively used in Mesoamerica beginning largely at this time, the middle of the first century BC.”

- 13. Welch, “A Steady Stream,” 274.

- 14. See Book of Mormon Central, “Did Ancient Israelites Write in Egyptian? (1 Nephi 1:2),” KnoWhy 4 (January 5, 2016); Book of Mormon Central, “Why Are Horses Mentioned in the Book of Mormon? (Enos 1:21),” KnoWhy 75 (April 11, 2016); Book of Mormon Central, “Why was Coriantumr’s Record Engraved on a ‘Large Stone’? (Omni 1:20),” KnoWhy 77 (April 13, 2016); Book of Mormon Central, “How Can Barley in the Book of Mormon Feed Faith? (Mosiah 9:9),” KnoWhy 87 (April 27, 2016); Book of Mormon Central, “What is the Nature and Use of Chariots in the Book of Mormon? (Alma 18:9),” KnoWhy 126 (June 21, 2016).

- 15. H. Curtis Wright, “Introduction,” in John A. Tvedtnes, The Book of Mormon and Other Hidden Books: “Out of Darkness and Unto Light” (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2000), ix–xii, similarly tells the story of a family in the Midwest which was bombarded with critical material dismissing the ancient practice of writing on metal plates, a practice which was already well-attested to at the time of the criticism.

KnoWhy Citation

Related KnoWhys

Subscribe

Get the latest updates on Book of Mormon topics and research for free