You are here

What was the Great and Terrible Gulf in Lehi’s Dream?

1 Nephi 12:18

The Know

Lehi’s dream is famous. Its imagery influenced almost all Book of Mormon writers, and it continues to teach people today many vivid lessons about the way of righteous living.

In his vision, Lehi saw a river that separated the tree of life from a great and spacious building (1 Nephi 8:26). He also saw that many people “were drowned in the depths of the fountain” as they felt their way through the mists of darkness aiming to get into that “strange building” (1 Nephi 8:31–33).

As his father’s dream was soon unfolded to Nephi, he also saw that fountain. Nephi said it was filled with “filthy water” and its depths “are the depths of hell” (1 Nephi 12:16). He called this “a great and a terrible gulf,” which he equated with “the word of justice of the Eternal God” that divides the righteous from the wicked (1 Nephi 12:18). As Nephi explained this to his brothers, the “awful gulf” was “a representation of that awful hell prepared for the wicked” (1 Nephi 15:26–29).

One way to approach Lehi’s dream is to see it as illuminating the "two ways" doctrine: the narrow way to the tree and the broad ways that lead to destruction. But what’s interesting is that Lehi’s dream gives us a depiction of the no-man’s land that lies between these two ways.

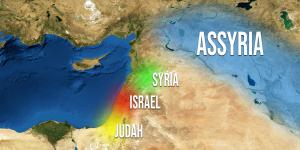

To understand the force of this image, it is logical and compelling to compare the things seen in the dream with geographical realities found in Arabia, where Lehi and his family were traveling when he had his dream.

Hugh Nibley was among the first to make these comparisons in his groundbreaking 1950 Improvement Era series “Lehi in the Desert.” He compared the gulf of Lehi’s dream to the wadis—deep canyons and narrow valleys—found in the Arabian mountains:

All who have traveled in the desert know the feeling of utter helplessness and frustration at finding one’s way suddenly cut off by one of those appalling canyons with perpendicular sides—nothing could be more abrupt, more absolute, more baffling to one’s plans, and so will it be with the wicked in a day of reckoning.1

Professor S. Kent Brown, who had traveled extensively in this region, developed this connection further in 2002. As Brown points out, usually there is a river or streambed running through the wadi. “After rains, the seasonal streams in the wadis fill with mud and debris,” which readily relates to the “filthy water” in 1 Nephi 12:16 and the “filthiness” in 15:26–27.”2

Moreover, the Valley of Lemuel, where Lehi had his dream, was likely one of these wadis. Hiding there obviously had its advantages but also its risks.

Recently, it occurred to a pair of Latter-day Saint explorers, standing in one of those canyons, that its steep walls and canyon creek might have brought to life the symbolism found in Lehi’s vision: “The high vertical walls of the gulf would be a good type for the depths of hell, since there would be no way back up and anyone who fell from the walls of the canyon could not survive.”3

The Why

These details tell us why Lehi’s dream was so powerful to him and to his posterity. Sudden desert storms, causing fatal flash floods, are feared by all wise travelers, such as Lehi. Staying out of harm’s way was of paramount importance.

These images were not fictions, but reflected realities. As Hugh Nibley reasoned, “The substance of Lehi’s dreams is highly significant, since men’s dreams necessarily represent, even when inspired, the things they see by day, albeit in strange and wonderful combinations.”4 Lehi traveled in Arabia by day, and he dreamed in terms of those ominous exposures by night.

As Lehi’s dream reflects the realities of life in Arabia, it would seem Lehi knew Arabia intimately: “Lehi’s dream, perhaps more than any other segment of Nephi’s narrative, takes us into the ancient Near East,” Brown reasons, “for as soon as we focus on certain aspects of Lehi’s dream, we find ourselves staring into the ancient world of Arabia. Lehi’s dream is not at home in Joseph Smith’s world but is at home in a world preserved both by archaeological remains and in the customs and manners of Arabia’s inhabitants.”5

In Arabia, deep chasms are filled with muddy water, separating travelers from their destination. This is the gulf of filthy water, the gulf of sin and unrighteousness, which separates the righteous from the wicked. This sweeping force struck Lehi and Nephi vividly as a powerful image of the natural justice of God, and these reasons help modern readers understand how and why the dream of Lehi has powerfully awakened, warned, and guided its numerous readers all around the world.

Further Reading

George Potter and Richard Wellington, Lehi in the Wilderness: 81 New, Documented Evidences that the Book of Mormon is a True History (Springville, Utah: Cedar Fort Publishing, 2003), 41–49.

S. Kent Brown, “New Light From Arabia on Lehi’s Trail,” in Echoes and Evidences of the Book of Mormon, ed. Donald W. Parry, Daniel C. Peterson, and John W. Welch (Provo, Utah: FARMS, 2002), 64–69.

Hugh Nibley, Lehi in the Desert/The World of the Jaredites/There Were Jaredites, The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley: Volume 5 (Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1988), 43–46.

- 1. Hugh Nibley, Lehi in the Desert/The World of the Jaredites/There Were Jaredites, The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley: Volume 5 (Salt Lake City and Provo, Utah: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1988), 46.

- 2. S. Kent Brown, “New Light From Arabia on Lehi’s Trail,” in Echoes and Evidences of the Book of Mormon, ed. Donald W. Parry, Daniel C. Peterson, and John W. Welch (Provo, Utah: FARMS, 2002), 65 (Italics added).

- 3. George Potter and Richard Wellington, Lehi in the Wilderness: 81 New, Documented Evidences that the Book of Mormon is a True History (Springville, Utah: Cedar Fort Publishing, 2003), 49.

- 4. Nibley, Lehi in the Desert, 43.

- 5. Brown, “New Light From Arabia,” 64.

KnoWhy Citation

Related KnoWhys

Subscribe

Get the latest updates on Book of Mormon topics and research for free