You are here

Why Did Joseph Write His Famous Letter from Liberty Jail?

Doctrine and Covenants 121:1

The Know

The letter Joseph Smith wrote in Liberty Jail between March 20 and 22, 1839, is perhaps his most famous letter: substantial excerpts from it have been canonized as Doctrine and Covenants 121, 122, and 123. These important sections contain some especially well-known and memorable passages. But few have ever read the letter in its entirety, and thus many do not realize that it also contains further words of advice and inspiration that are well worth study, reflection, and consideration.

Joseph wasn’t the only luminary in history to write from the confines of a cell. Martin Luther King Jr.,1 Nelson Mandela,2 John Brown,3 Titus Brandsma,4 Boethius,5 and of course, the Apostle Paul6 all wrote important, impactful letters from prison. Joseph Smith’s letter from Liberty Jail is among these famous letters written under such confining circumstances. As a pair of Latter-day Saint scholars recently observed, “The letter from Liberty Jail represents a distinctive Latter-day Saint contribution to the canon of great prison literature, … offering [among other things] poignant reflections on power by those who suffer its abuses.”7

Why did these people write? All these letters are passionate pleas for justice, reform, and vindication. Many of them give instructions and offer philosophical or religious guidance. While evoking these same themes, Joseph Smith’s letter goes even further because it conveys some of the most inspiring and eternally poignant truths and revealed instructions ever recorded.

What specifically motivated Joseph to write this profound letter after five months of horrific confinement in prison? In many ways his world was in shambles. His people, including his own wife and children, had been driven out of Missouri to the Illinois side of the Mississippi River at Quincy.8 But they were safe, and Joseph had recently heard from them. Hope wasn’t entirely lost. These and other circumstances were clearly on Joseph’s mind as he crafted this memorable epistle.

To feel the full impact of Joseph’s words—and why he said them—the letter needs to be read in its entirety.9 It can be especially powerful to hear the letter read aloud, as done by John W. Welch in a recently released YouTube video:

The Why

Some of his reasons for writing are obvious and well known, especially the parts of the letter that have been canonized as Doctrine and Covenants 121, 122, and 123. Other important reasons may be less apparent to those who have not read the entire letter in its historical context. Consider the following ten reasons:

1. Joseph had just received letters from his wife, Emma; from Bishop Partridge; and from an Iowa land-developer, Isaac Galland.10 Joseph wrote to keep open channels of communication with them. Aware of their tribulations and grateful for what they had said and asked, Joseph assured them that “every species of wickedness and cruelty practiced upon us will only tend to bind our hearts together and seal them together in love.”11

2. Joseph wrote sympathetically to acknowledge how much all the Saints had been suffering. He also wrote to tell them that those imprisoned were not happy with their lawyers because they had ineffectively debated with the state over the meaning of habeas corpus and the application of Article 13, Section 11 of the Missouri Constitution of 1820. Apparently, the state had unjustifiably argued that the general need for public safety overrode the prisoners’ individual liberty—without showing the slightest probable cause.

3. Joseph wrote to celebrate the virtue of friendship and to express gratitude for friends. While Joseph was separated from them, his appreciation for true friends had grown even deeper. Those “who have not been enclosed in the walls of prison without cause or provocation,” the Prophet related, “can have but little idea how sweet the voice of a friend is; one token of friendship from any source whatever awakens and calls into action every sympathetic feeling; … it seizes the present with the avidity of lightning; it grasps after the future with the fierceness of a tiger; … until finally all enmity, malice and hatred, and past differences, misunderstandings and mismanagements are slain victorious at the feet of hope.”

4. Joseph wrote to tell of a nearly successful attempt to escape from prison. After diligent effort on their part, the small tool they were using to escape finally broke, and somehow they were detected: “Unfortunately for us, the timber of the wall being very hard, our auger handles gave out; … we applied to a friend, and … we had everything in readiness, but the last stone, and we could have made our escape in one minute, and should have succeeded admirably, had it not been for a little imprudence or over-anxiety on the part of our friend.”

5. He wrote to vent his extreme displeasure with Governor Boggs, who had unilaterally issued the Extermination Order, driving the Saints from Missouri at threat of death—in the dead of winter. “What is Boggs or his murderous party, but wimbling willows upon the shore to catch the flood-wood?” He wrote to assure all Church members, saying that they should not despair or “say that our cause is down because renegades, liars, priests, thieves and murderers … have poured down, from their spiritual wickedness in high places, and from their strongholds of the devil, a flood of dirt and mire and filthiness and vomit upon our heads.”

6. He wrote to tell the Saints that public opinion appeared to be shifting sympathetically toward the members of the Church: “As nigh as we can learn, the public mind has been for a long time turning in our favor, and the majority is now friendly.” The fact that a Missouri sheriff would soon sell Joseph and the other prisoners a horse and allow them to leave supports Joseph’s sense of expanding sympathy and good will of many people in Missouri.

7. Joseph wrote to rebuke “the wickedness” of Samson Avard and the Danites, decrying their secret operations.12 Joseph was in no way supportive of the self-appointed vigilantes and warned all Church members to shun “the impropriety of the organization of bands or companies.” Instead, he wrote, “Let our covenant be that of the Everlasting Covenant, as is contained in the Holy Writ and the things that God hath revealed unto us.” He also advised the Church to not fall prey to the kinds of economic arrangements that had left the Saints vulnerable in Kirtland: “We further suggest for the considerations of the Council, that there be no organization of large bodies upon common stock principles, in property, or of large companies of firms, until the Lord shall signify it in a proper manner, as it [otherwise] opens such a dreadful field for the avaricious, the indolent, and the corrupt hearted to prey upon the innocent and virtuous, and honest.”13

8. He wrote to instruct the Church members where to seek safety, or settle next. He encouraged the Church officers to look to Iowa and Nauvoo. Federal land sales would soon be opening up in southeast Iowa, and he favored being in contact with Isaac Galland, who had land to sell in Nauvoo. In the meantime, he encouraged Church members to settle along the corridor between Kirtland, Far West, and Illinois in order to keep the Saints unified in “the spirit of the gathering, that they fall into the places and refuge of safety that God shall open unto them.”

9. Joseph wrote to instruct people to keep specific records of their losses in Missouri. This part of the letter is found today in D&C 123. Joseph would soon end up taking these claims to Washington D.C., hoping that federal law would come to the aid of the Saints in consequence of their being denied the right to purchase federal land. The Saints had been denied this right under the powers of the state of Missouri without due process—they had even been “prevented … from introducing our evidence” in court.14

That, of course, violated a fundamental guarantee given to all citizens of the United States in the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment to the US Constitution.

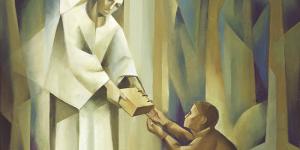

10. Above all, Joseph wrote to bear his personal testimony, especially of God, Jesus Christ, and the scriptures. Here—more than at any other time on record—Joseph bore his pure and solemn testimony, assuring his people that God was still speaking to him and to them. He wrote:

Hell may pour forth its rage like the burning lava of Mount Vesuvius, or of Etna, or of the most terrible of the burning mountains; and yet shall “Mormonism” stand. Water, fire, truth and God are all realities. Truth is “Mormonism.” God is the author of it. He is our shield. It is by Him we received our birth. It was by His voice that we were called to a dispensation of His Gospel in the beginning of the fullness of times. It was by Him we received the Book of Mormon; and it is by Him that we remain unto this day; and by Him we shall remain, if it shall be for our glory; and in His Almighty name we are determined to endure tribulation as good soldiers unto the end.

He concluded his long letter by again testifying, in the face of all adversity:

We say [1] that God is true; [2] that the Constitution of the United States is true; [3] that the Bible is true; [4] that the Book of Mormon is true; [5] that the Book of [Doctrine and] Covenants is true; [6] that Christ is true; [7] that the ministering angels sent forth from God are true, and [8] that we know that we have an house not made with hands eternal in the heavens, whose builder and maker is God.

Further Reading

Dean C. Jessee and John W. Welch, “Revelations in Context: Joseph Smith’s Letter from Liberty Jail, March 20, 1839,” BYU Studies Quarterly 39, no. 3 (2000): 125–145.

Justin R. Bray, “Within the Walls of Liberty Jail,” in Revelations in Context: The Stories Behind the Sections of the Doctrine and Covenants, ed. Matthew McBride and James Goldberg (Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2016), 256–263.

Ryan J. Wessel, “The Textual Context of Doctrine and Covenants 121–23,” Religious Educator 13, no. 1 (2012): 102–115.

- 1. Martin Luther King Jr., “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” April 16, 1963, online at https://letterfromjail.com.

- 2. Sahm Venter, ed., The Prison Letters of Nelson Mandela (New York, NY: W. W. Norton, 2018).

- 3. John Brown, “Letters from Jail in the Week before His Execution,” online at https://www.bartleby.com.

- 4. Titus Bradnsma, “The Last Days of Titus—Letters Written in Prison,” November 1941 to July 1942, online at https://www.ewtn.com.

- 5. See “Bothius and the Consolation of Philosophy,” The School of Life, online at https://www.theschooloflife.com.

- 6. Joel Ryan, “What Are the Prison Epistles?,” online at https://www.christianity.com.

- 7. Patrick Q. Mason and J. David Pulsipher, Proclaim Peace: The Restoration’s Answer to an Age of Conflict (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, Brigham Young University, 2021), 3.

- 8. See Susan Easton Black, Glenn Rawson, and Dennis Lyman, eds., The Quincy Miracle: A Rescue Never to be Forgotten (Sandy, UT: History of the Saints, 2016) for additional information and context regarding these events.

- 9. For the full letter, see Dean C. Jessee and John W. Welch, “Revelations in Context: Joseph Smith’s Letter from Liberty Jail, March 20, 1839,” BYU Studies Quarterly 39, no. 3 (2000): 125–145. On the canonization process of this letter, see Kathleen Flake, “Joseph Smith’s Letter from Liberty Jail: A Study in Canonization,” Journal of Religion 92, no. 4 (2012): 515–526.

- 10. For more on the context of the letter, see Justin R. Bray, “Within the Walls of Liberty Jail,” in Revelations in Context: The Stories Behind the Sections of the Doctrine and Covenants, ed. Matthew McBride and James Goldberg (Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2016), 256–263; Steven C. Harper, Doctrine and Covenants Contexts (Springville, UT: Book of Mormon Central, 2021), 315–324, on sections 121, 122, and 123.

- 11. All quotations in the list are from the letter as transcribed in Jessee and Welch, “Revelations in Context,” 125–145.

- 12. For background on the Danites, see Alexander L. Baugh, “Danites,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, ed. Arnold K. Garr, Donald Q. Cannon, Richard O. Cowan (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2000), 275.

- 13. On the economic difficulties in Kirtland, see Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did the Kirtland Safety Society Fail? (Doctrine and Covenants 64:21),” KnoWhy 604 (May 18, 2021).

- 14. For more details on these events, see Book of Mormon Central, “Why Were the Saints Driven from Missouri in the Fall of 1838? (Doctrine and Covenants 121:6),” KnoWhy 620 (October 11, 2021).

KnoWhy Citation

Related KnoWhys

Subscribe

Get the latest updates on Book of Mormon topics and research for free