You are here

Why Did Some in Lehi’s Time Believe that Jerusalem Could Not Be Destroyed?

1 Nephi 2:13

The Know

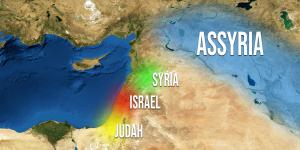

After Sennacherib, the powerful king of Assyria, conquered the northern kingdom of Israel in 722 B.C. and deported much of its population, he invaded the southern kingdom of Judah in 701. Although he destroyed several well-fortified cities and carried away thousands of people, he was not successful in conquering Jerusalem.

At that time, a righteous king named Hezekiah ruled over Jerusalem, and God promised to “defend this city [Jerusalem], to save it, for mine own sake, and for my servant David’s sake.” The Lord kept his promise to King Hezekiah, for “it came to pass that night, that the angel of the Lord went out, and smote in the camp of the Assyrians an hundred fourscore and five thousand” (2 Kings 19:34–35).

Jerusalem miraculously survived an invasion attempt by Assyria, the greatest empire in the world at that time. For this reason, when the Babylonian armies laid siege to Jerusalem about a hundred years later, there were many in the city who firmly believed it could not be conquered. Laman and Lemuel, the sons of the prophet Lehi, had believed similarly when their own father was called to be a prophet of God. Although many prophets, including their father, were prophesying to the contrary, they did not “believe that Jerusalem, that great city, could be destroyed according to the words of the prophets” (1 Nephi 2:13).

Sennacherib during his Babylonian war, relief from his palace in Nineveh. Image via Wikimedia Commons

BYU Religious Education professors David Rolph Seely and Fred E. Woods identified six factors that may have contributed to this deeply-held, but ultimately erroneous, belief that Jerusalem could not possibly be destroyed. They noted that:

1) The spiritual traditions regarding Jerusalem suggested to many that because the city was God’s holy habitation on earth, the site of His house, the Temple of Jerusalem, He would naturally protect it from desecration and destruction. According to tradition, the temple built by Solomon had been erected on the location where Abraham had nearly sacrificed Isaac. The temple had stood for three hundred years and was seen as a powerful symbol of the presence of the Lord, their Savior, in the city.

2) Many appear to have misunderstood the nature of the Lord’s covenant with David, especially in regard to what it meant for the protection of David’s city, Jerusalem. The Lord had promised David: “Thine house and thy kingdom shall be established for ever before thee: thy throne shall be established forever” (2 Samuel 7:16; see Psalm 89:3–4). This part of the Davidic covenant was unconditional and was ultimately fulfilled by the coming of Jesus of Nazareth as the Messiah from the lineage of David (Matthew 1:1–17).

However, some scriptural passages connected the Davidic covenant with Jerusalem, the city of David (see Psalm 132:13, 17–18), and prophets such as Isaiah declared that the Lord would protect His holy city (Isaiah 31:4–5). But the Lord had made it clear, through his prophets, that these promises of protection were conditional, depending on the people’s obedience to God’s commandments (1 Kings 6:12–13; 9:6–7).

3) The miraculous deliverance of Jerusalem from the Assyrians in the days of King Hezekiah (2 Kings 18–19), discussed above, strengthened the belief that the Lord would preserve Jerusalem and its temple from all enemies.

4) Hezekiah had gone to great lengths to fortify Jerusalem and prepare it for siege. He had massive walls and towers built (2 Chronicles 32:2–8) and created a water source inside the city that would help them endure long sieges (2 Kings 20:20; 2 Chronicles 32:4, 30). These robust fortifications would surely have contributed to a feeling of impregnability.

5) Not many years before Lehi left Jerusalem, Judah’s King Josiah had undertaken a massive religious reformation that centralized worship around the Temple of Jerusalem. He attempted to eradicate the worship of idols and foreign gods and led the people in a renewal of their covenants with Jehovah (2 Kings 22–23). These reforms may have led some people to hold an exaggerated view of their own righteousness and favor in God’s eyes.

6) Although there were many prophets, like Jeremiah and Lehi, who were prophesying of the destruction of Jerusalem, there were also false prophets, such as Hananiah (Jeremiah 28:15) who gave the opposite message—that God would preserve them from their enemies. They were in the business of telling the people and their leaders what they wanted to hear and not what the Lord wanted them to know, so many hearkened unto their words instead of to the words of the true prophets.1

The Why

Although many elements likely contributed to the undue sense of security and divine approval held by those at Jerusalem, the most basic factor was that they were unwilling to listen to the true and living prophets of God.

The fact that false prophets were preaching pleasing words to the people understandably made following the true word of the Lord more complicated. As BYU Professor Aaron Schade noted: “To make things more difficult for the people, at this time when ‘true prophets’ of God were receiving divine direction to warn the people of Judah to repent, as well as to surrender themselves peacefully over to the Babylonians, others were preaching the safety and impregnability of Judah.”2

Laman and Lemuel, like those who dwelt at Jerusalem, struggled to discern the true word of the Lord, even though their own father was a true prophet. Their hardened hearts and overconfidence blinded them to the real danger they would have faced had they not followed their father into the wilderness. Thus, Nephi had the following to report on the reactions of the Jews to his father’s preaching, an attitude which ultimately led them to destruction, along with their beloved city:

And it came to pass that the Jews did mock him because of the things which he testified of them; for he truly testified of their wickedness and their abominations; … And when the Jews heard these things they were angry with him (1 Nephi 1:19–20).

Further Reading

David Rolph Seely and Fred E. Woods, “How Could Jerusalem, ‘That Great City,’ Be Destroyed,” in Glimpses of Lehi’s Jerusalem, ed. John W. Welch, David Rolph Seely, and Jo Ann H. Seely (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2004), 595–610.

Aaron P. Schade, “The Kingdom of Judah: Politics, Prophets, and Scribes,” in Glimpses of Lehi’s Jerusalem, ed. John W. Welch, David Rolph Seely, and Jo Ann H. Seely (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2004), 299–336.

Book of Mormon Central, “How Can the Old Testament Covenants Help Us Understand the Book of Mormon? (1 Nephi 2:12–13),” KnoWhy 363 (September 12, 2017).

Taylor Halverson, “Covenant Patterns in the Old Testament and the Book of Mormon,” presentation given at the 2017 BMAF–BMC Book of Mormon Conference, online at bookofmormoncentral.org.

- 1. These six points were adapted from David Rolph Seely and Fred E. Woods, “How Could Jerusalem, ‘That Great City,’ Be Destroyed,” in Glimpses of Lehi’s Jerusalem, ed. John W. Welch, David Rolph Seely, and Jo Ann H. Seely (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2004), 595–610.

- 2. Aaron P. Schade, “The Kingdom of Judah: Politics, Prophets, and Scribes,” in Glimpses of Lehi’s Jerusalem, ed. John W. Welch, David Rolph Seely, and Jo Ann H. Seely (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2004), 308.

KnoWhy Citation

Related KnoWhys

Subscribe

Get the latest updates on Book of Mormon topics and research for free