You are here

How Was Nephi Similar to Joseph of Egypt?

1 Nephi 18:18

The Know

The writers of the Book of Mormon often alluded to the Old Testament to help people understand their message on more levels and to make more connections to the scriptures and to their own lives. They knew that highlighting the similarities between the events they were writing about and stories from the Old Testament (Plates of Brass) would help the reader understand both stories better. Nephi often alluded to the story of Joseph when writing about his own life, and these allusions help us understand both Nephi and Joseph in a new way.1

Literary scholar Alan Goff has noted, for example, that when Laman complained against Nephi, he brought two accusations against him: “[1] Nephi wants to usurp the authority of the elder brothers, and [2] he lies to them about being guided by God.”2 Laman clearly did not believe Nephi’s claims “that the Lord has talked with him, and also that angels have ministered unto him.” Laman was convinced Nephi was lying and doing “many things by his cunning arts, that he may ... make himself a king and a ruler over us” (1 Nephi 16:38).3

Goff has observed that even though “Laman has witnessed angelic intervention and heard words from the angel proclaiming Nephi’s eventual rule (1 Nephi 3:29), he claims that Nephi is unrighteously trying to rule over them.”4 Joseph of Egypt was in a similar situation. When he had a divine manifestation in a dream and was told that he would someday rule over his brothers, they responded, “shalt thou indeed reign over us? or shalt thou indeed have dominion over us? And they hated him yet more for his dreams and for his words” (Genesis 37:8). Joseph’s brothers thought that he wanted to usurp their authority and that he was lying about being guided by God, the same charges Laman leveled against Nephi.5

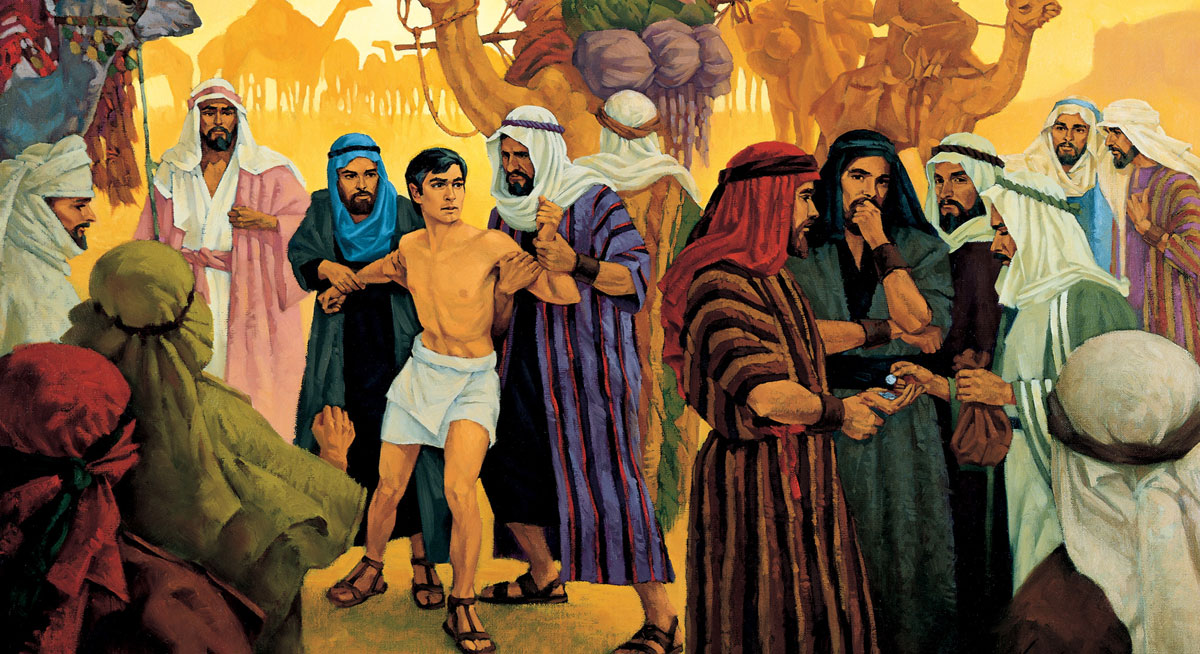

Laman and Lemuel also tied Nephi up, planning on leaving him “in the wilderness to be devoured by wild beasts” (1 Nephi 7:16). As Goff has noted, “the format of this story is similar to the story of that other Joseph whose brothers intend to put him into a pit and leave him there to die rather than killing him outright and have his blood on their hands.”6 Joseph’s brothers’ false claim that Joseph had been eaten by wild beasts (see Genesis 37:20, 33), would only have been plausible if there really were hungry wild beasts around.7

Thus, Reuben’s suggestion that they leave Joseph in a pit (v. 22) was likely interpreted by the brothers as a means of killing him. They were leaving him to be devoured by wild beasts, just as Laman and Lemuel would eventually try to do to Nephi.8 In both the case of Joseph and Nephi, however, the older brothers repented. Joseph's brothers sold him into slavery instead of killing him (Genesis 37:22–24), and Nephi’s brothers, after being chastened by the Lord, also repented and spared Nephi (1 Nephi 16:39).9

Even some of the language of 1 Nephi is similar to what is found is the Joseph narrative. Nephi stated that Lehi and Sariah’s “grey hairs were about to be brought down to lie low in the dust; yea, even they were near to be cast with sorrow into a watery grave” (1 Nephi 18:18). The image of Lehi and Sariah’s grey hairs being brought down with sorrow to the grave is exactly what we find in the Joseph narrative.10 Genesis repeatedly states that if Jacob lost another child, it would bring down his “gray hairs with sorrow to the grave” (Genesis 42:38; 44:29, 31). These three verses are the only time these words appear in the scriptures, making it more likely that the connection between the two stories was intentional.11

The Why

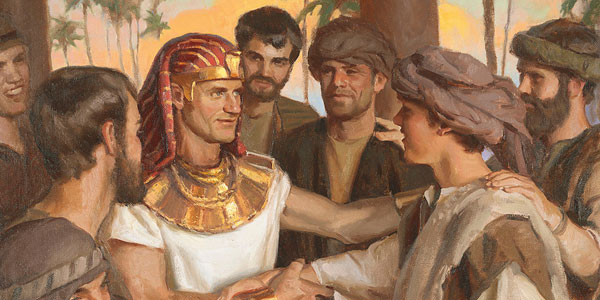

Because 1 Nephi is one of the oldest surviving texts that comments on a biblical story (outside the Bible itself) it gives us insights on the Joseph story that we could gain in no other way. The Bible does not tell us how Joseph felt as he headed south across the desert towards Egypt. However, we do know how Nephi felt as he headed south across the desert to an unknown promised land.

Nephi, at first, seems to have wondered why he was being asked by God, through his father, to suffer through something so difficult. However, he said, “I did cry unto the Lord; and behold he did visit me, and did soften my heart that I did believe all the words which had been spoken by my father” (1 Nephi 2:16). God softened Nephi’s heart, helping him to know that he was doing what God wanted him to do and was where God wanted him to be.

Although we do not know for sure whether Joseph had a similar experience, it seems very likely that he, like Nephi, wondered why he had to go through something so difficult. Yet he, like Nephi, seems to have received an assurance that God knew him and was taking care of him. Near the end of Joseph’s life, he told his brothers, “ye thought evil against me; but God meant it unto good, to bring to pass, as it is this day, to save much people alive” (Genesis 50:20). He knew that God had been with him through all his afflictions, and that even though his brothers had meant to harm him, God had made sure everything worked out well in the end.

Like Joseph and Nephi, we can also feel the reassurance from the Lord that even though we may not know every turn our life may take, we can know that God will help things to work out. This does not mean that we will not experience suffering between now and the end of our journey (Joseph and Nephi did), but we can know that God will consecrate our afflictions for our gain (see 2 Nephi 2:2). The words of Dallin H. Oaks apply to Joseph, to Nephi, and to us: “the Lord will not only consecrate our afflictions for our gain, but He will use them to bless the lives of countless others.”12

Further Reading

Grant Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon: A Reader’s Guide (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2010), 42–44.

Alan Goff, “A Hermeneutic of Sacred Texts: Historicism, Revisionism, Positivism, and the Bible and Book of Mormon,” (MA dissertation, Brigham Young University, 1989), 104–132.

Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 1:47.

- 1. For an overview of this topic this, see Alan Goff, “A Hermeneutic of Sacred Texts: Historicism, Revisionism, Positivism, and the Bible and Book of Mormon,” (MA dissertation, Brigham Young University, 1989), 104–132. For a more recent take on the topic, see Grant Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon: A Reader’s Guide (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2010), 42–44. For a summary, see Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 1:47.

- 2. Goff, “A Hermeneutic of Sacred Texts,” 104.

- 3. Goff, “A Hermeneutic of Sacred Texts,” 104.

- 4. Goff, “A Hermeneutic of Sacred Texts,” 104–105.

- 5. Goff, “A Hermeneutic of Sacred Texts,” 105.

- 6. Goff, “A Hermeneutic of Sacred Texts,” 60.

- 7. For more on this, see Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon, 42.

- 8. Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon, 42.

- 9. Goff, “A Hermeneutic of Sacred Texts,” 105.

- 10. Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon, 43.

- 11. Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon, 43. It is likely that Lehi made connections between their experiences and Joseph’s experiences as well, since he named one of the sons born to him in the wilderness after Joseph. See Hugh Nibley, Lehi in the Desert/The World of the Jaredites/There Were Jaredites, The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley, Volume 5 (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1988), 42.

- 12. Dallin H. Oaks, “Give Thanks in All Things,” Ensign, 2003, online at lds.org.

KnoWhy Citation

Related KnoWhys

Subscribe

Get the latest updates on Book of Mormon topics and research for free