You are here

What Is the “Skin of Blackness” in the Book of Mormon?

2 Nephi 5:21

The Know

In the aftermath of Lehi’s death, Nephi and those who followed him were forced to flee from Laman and Lemuel because the two brothers sought, once again, to kill him. Nephi and his people, however, established a prosperous colony, complete with a temple, where they followed the law of Moses and were blessed according to the covenants the Lord made with Lehi and his family (2 Nephi 5:1–17).

In contrast, Nephi reported that his brothers were “cut off from the presence of the Lord” and that a “cursing … even a sore cursing” came upon them “because of their iniquity.” Consequently, their hearts became hardened like flint, and whereas once “they were white, and exceedingly fair and delightsome, … the Lord did cause a skin of blackness to come upon them” (2 Nephi 5:21). Another account, presumably the large plates of Nephi, recorded that the Lord “cursed, and … set a mark on” the Lamanites, and thus “the skins of the Lamanites were dark, according to the mark which was set upon their fathers, which was a curse upon them” (Alma 3:6, 14).

Church Disavows Theories of Black Skin as a Curse

For many modern readers, these and similar passages in the Book of Mormon are understandably jarring in their seemingly “racist concepts of nonwhite racial inferiority as contrasted with white racial superiority.”1 In the past, many readers and writers have accepted such racial connotations without question, but a 2013 essay authorized by the First Presidency published on the Church’s website declares unequivocally, “Today, the Church disavows the theories advanced in the past that black skin is a sign of divine disfavor or curse.”2

Despite this pronouncement, some scholars persist in reading the Book of Mormon through an old racial lens, albeit often with the twist that this lens actually subverts the racism of the nineteenth century.3 More careful scrutiny, however, indicates that the text does not comport with modern racial perspectives at all. Euro-American sources from the 1800s most frequently describe Native Americans as having red or copper skin, and these are the descriptions typically used by Joseph Smith, Oliver Cowdery, and other early Latter-day Saints as well.4 Yet as Hugh Nibley first pointed out in the 1950s, “there is no mention in the Book of Mormon of red skins versus white; indeed, there is no mention of red skin at all.”5

Dark/Black Skin in Ancient Near Eastern Symbolism

Instead, the Book of Mormon consistently contrasts black or dark skins with white or fair skins in ways consistent with ancient Near Eastern symbolism. For instance, Nibley noted, “With the Arabs, to be white of countenance is to be blessed and to be black of countenance is to be cursed.”6 This can be seen in the Quran, in which the day of judgment is described as “the Day when faces whiten and faces blacken.”7 Nibley noted a similar idiom in an ancient Egyptian text as well, which described being ḥḏ-ḥr, “white of countenance,” and being šw m snk.wt, “free from darkness.”8

Kerry Hull has recently drawn attention to similar expressions in early Jewish and Christian literature that are not racist but symbolic and are often drawn from poetic imagery in the Bible itself.9 For example, Origen and Augustine drew upon Song of Solomon 1:5 (“I am black, but comely [that is, fair or beautiful]”) and paired it with Song of Solomon 8:5 LXX (“Who is this that comes up all white”) as a metaphor for people who are black with sin but are washed white through repentance and baptism (compare 3 Nephi 2:15–16). Origen wrote, “She is called black, however, because she has not yet been purged of every stain of sin … nevertheless she does not stay dark-hued, she is becoming white.”10 Some early Christians metaphorically referred to the dark or black skin of Ethiopians in such analogies.11

Perhaps the most direct and enlightening ancient Near Eastern parallel to the Book of Mormon’s “skin of blackness” in terms of date, circumstance, and language is found in the Succession Treaty of Esarhaddon, recently discussed by T. J. Uriona.12 This treaty was sent out to Assyrian vassals, including Judah, in around 672 BC to establish Esarhaddon’s son Assurbanipal as the legitimate successor—despite the fact that he was not the eldest son.13 As was customary in ancient Near Eastern treaties and covenants, curses were pronounced upon those who would violate this treaty’s terms. One of the curses in the document states, “May they [the gods] make your skin and the skin of your women, your sons and your daughters—dark. May they be as black as pitch and crude oil.”14

The biblical prophet Nahum, one of Lehi’s contemporaries, appears to have alluded to this very curse in a “subversive reversal” of the imagery, applying it to the fall of the Assyrian Empire itself around 612 BC: “The faces of [the Assyrians] all gather blackness” (Nahum 2:10).15 Likewise, in Lamentations (traditionally ascribed to the prophet Jeremiah) similar imagery is used of the Nazarites after Jerusalem was destroyed: “Her Nazarites were purer than snow, they were whiter than milk … [but now their] visage is blacker than a coal,” later adding, “Our skin was black like an oven” (Lamentations 4:7–8; 5:10).

In its Assyrian context, “skin black as pitch” appears to be a motif for death and destruction.16 Its reappropriation in Lamentations, according to Gideon Kotze, may not refer to literal death but instead could indicate that the people have become “dead men walking.”17 Likewise, the “skin of blackness” Nephi describes falling upon the Lamanites was not necessarily physical but was given in the context of some people violating the Lord’s covenant and thereby being “cut off from the presence of the Lord,” bringing upon themselves the sore cursing that Lehi had warned of previously.18 In other words, the Lamanites had simply experienced what Alma later calls “spiritual death” and thus their souls were in spiritual darkness (Alma 42:9).

Symbolic Meaning of Black (or Dark) and White in the Book of Mormon

Clues throughout the Book of Mormon strongly support the symbolic interpretation of references to black, dark, and white “skins.” For instance, the earliest descriptions of people as either white or dark come in Nephi’s foundational vision.19 Rather than being literal references to skin color, these labels appear to figuratively link different people or groups back to the white and dark symbols of Lehi’s dream, in 1 Nephi 8.20 Likewise, throughout the Book of Mormon dark is frequently paired with terms such as filthy and loathsome that are clearly intended to describe the spiritual state of the Lamanites, not their lack of hygiene or physical attractiveness.21

Furthermore, throughout the rest of the text white, black, and dark are applied variously to objects, garments, skins, and people—always in ways consistent with symbolism associating white with purity, holiness, and righteousness while associating black or dark with impurity, unholiness, and the stain of sin.22 In most contexts throughout the Book of Mormon, it is clear that these terms are symbolic or metaphorical. Thus, as David M. Belnap observed, “metaphorical readings [of skin color passages] bring consistency to other Book of Mormon verses connecting lightness, delightsomeness, darkness, filthiness, and similar words to a person’s or a people’s spiritual state.”23

In addition, toward the end of his record, Nephi speaks of a future day when the remnant of the Lamanites would be “restored unto the knowledge of … Jesus Christ,” causing “their scales of darkness … to fall from their eyes; and … they shall be a white and a delightsome people” (2 Nephi 30:5–6).24 The imagery alludes to the sore cursing from 2 Nephi 5:21 being lifted, and Joseph Smith clarified this passage in the Nauvoo edition of the Book of Mormon to read “a pure and a delightsome people,” making it crystal clear that spiritual purity rather than skin color is what was intended.25

A Self-Imposed Dark Skin as a Mark

If a real difference between Nephites and Lamanites in physical skin color existed, it does not seem to have been very stark since any such difference goes completely unmentioned in several accounts in which it would be expected to have a noticeable impact on events.26 John L. Sorenson explained, “It is likely that the objective distinction in skin hue between Nephites and Lamanites was less marked than the subjective difference.”27 Some have suggested that Lamanites may have more heavily intermarried with Indigenous populations, or that their lifestyle darkened their skin due to greater sun exposure.28 These would have created a more subtle difference in skin tone that perhaps was exaggerated for symbolic purposes.

Others, pointing to the story of Amlicites, reason that any difference in physical appearance “was propagated by the Lamanites themselves … through marking their own skin.”29 The Amlicites “marked themselves with red in their foreheads after the manner of the Lamanites,” but this was interpreted as a fulfillment of the Lord’s declaration that “I will set a mark upon him that fighteth against thee and thy seed” despite the fact that they “set the mark upon themselves” (Alma 3:4, 13, 18). Nibley explained, “So natural and human was the process that it suggested nothing miraculous to the ordinary observer. … Here God places his mark on people as a curse, yet it is an artificial mark which they actually place upon themselves.”30

In recent years, several theories have given possible explanations of the nature of this artificial mark. For example, consider these three leading proposals:

1. Dark Skins as Garments

One theory, first proposed by Ethan Sproat and summarized by John W. Welch, suggests that “when [Alma] chapter 3 is read in its entirety, it becomes apparent that … the dark ‘skins’ were possibly animal skins worn as symbolic clothing, not their normal flesh.”31 In both the Book of Mormon and the Bible, skin can refer to animal skin garments, and in fact this appears to be the context in which the Lamanites’ skins are described as dark in Alma 3:5–6: “The Lamanites … were naked, save it were a skin which was girded about their loins. … And the skins of the Lamanites were dark, according to the mark which was set upon their fathers” (emphasis added). If this theory is correct, Welch noted, “the Lamanites and Amlicites were distinguishing themselves by the things they chose to wear or put upon themselves.”32

Sproat draws on the Israelite temple tradition, which used special temple garments that represented the coat of skins given to Adam and Eve when they left the Garden of Eden, and he notes that each of the major statements about Lamanite skin color comes in a temple context.33 Throughout the Book of Mormon, authors referred to both garments and skins in identical ways as symbols of one’s spiritual state. Among early Christians, the symbolism of Adam and Eve’s dark coat of skins was contrasted with a garment of light that they shed upon leaving the garden, with each garment symbolically representing the flesh—the coat of skins being the flesh in its mortal, sinful state, and the garment of light being symbolic of both the purified state after baptism and the glorified state of the Resurrection.34

2. Dark Skins as Body Paint

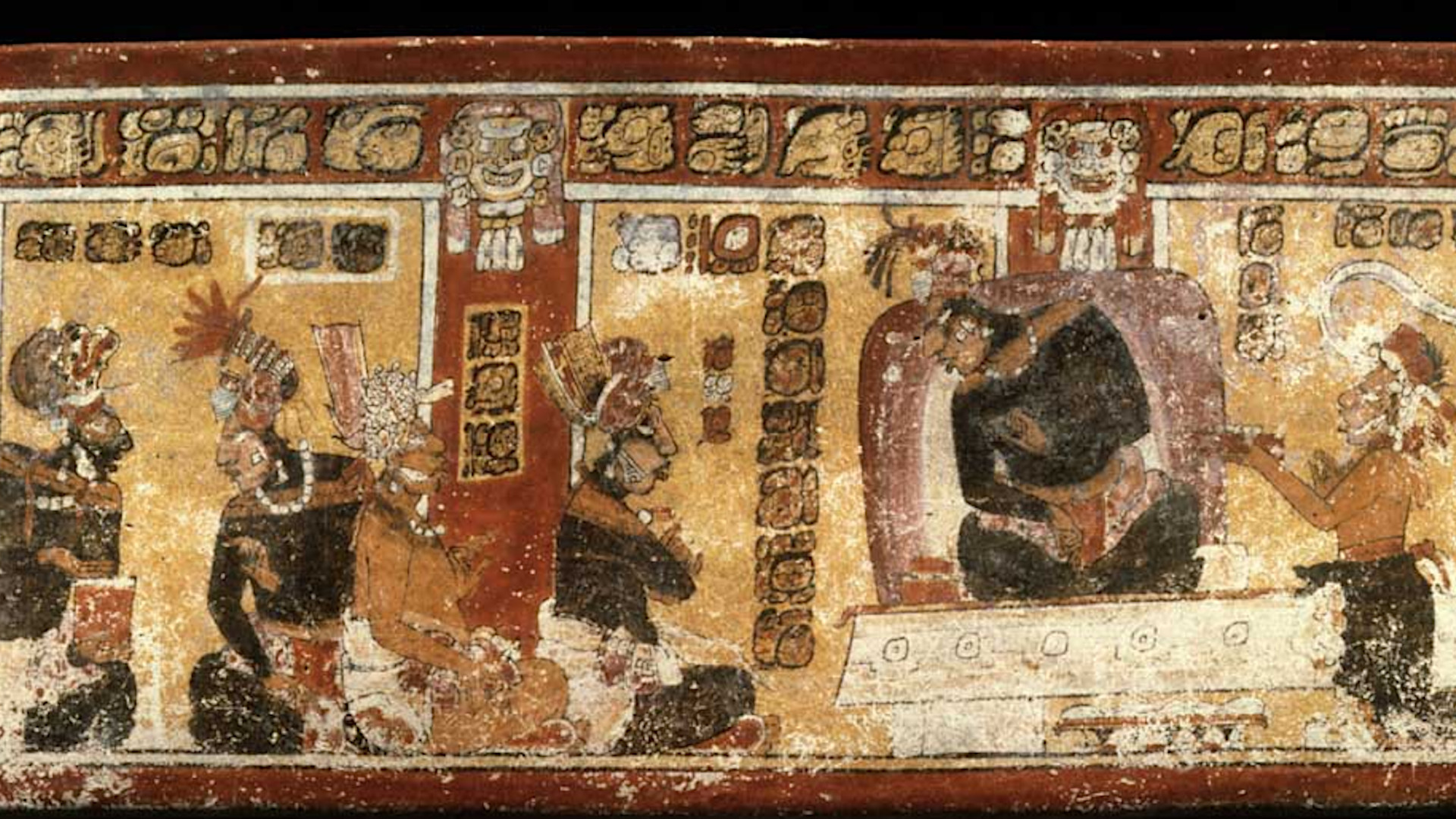

Another proposal, recently put forward by Gerrit M. Steenblik, is that the Lamanites marked themselves by painting their skin dark. Art from the Classic Maya period illustrates that many elites “darkened their skins with paints, stains, and pigments for ceremonial purposes and as camouflage for warfare, hunting, and plunder.”35 This fits with Nephi’s reference to a “skin of blackness” in close association to describing the Lamanites as hunters “in the wilderness for beasts of prey.” Furthermore, the first occasion in which Nephi and his people encountered the Lamanites after being separated from them was likely during their “wars and contentions” (2 Nephi 5:24, 34). The Amlicites also mark themselves in a military context (Alma 3:4).

Skin darkened by paint or staining could be associated with cursings through prewar rituals of whispering curses while applying the paint. Charcoal and soot were often used in these skin-darkening paints, which could have linked the paint-darkened skins to filthiness in the Nephites’ point of view.36 For some Maya ceremonies, ritual participants would fast for several days and “cover themselves with black paint or soot, only to be cleansed of the black soot—both physically and symbolically purified—at the end of the fast.”37 Perhaps something similar took place through the purifying ritual of baptism when some Lamanites had “their curse … taken from them, and their skin became white like unto the Nephites” (3 Nephi 2:15).

3. Dark Skins as Tattoos

Others have suggested that the mark could have been an ancient tattoo.38 Tattooing was known in the ancient Near East and in the Americas among various Indigenous tribes in both North and South America.39 In Mesoamerica, it can be documented from as early as 1400 BC among the Olmec and, later, the Maya, as the practice was continued up through the Spanish Conquest.40 Most tattooing in ancient America was black, but some evidence exists for red tattoos at Chichen Itza, thus accounting for both the black or dark skin of the Lamanites and the red mark of the Amlicites (Alma 3:4).41

Linguistically, “the language of ‘mark’ in the Book of Mormon could … relate to the word tattoo” since it originally meant “to write, paint, or mark.”42 Words with a similar range of meaning are attested in Mayan languages.43 In Hebrew, qaʿaqaʿ means “incision, imprintment, tattoo” and gets translated as “mark” in Leviticus 19:28: “Ye shall not … print any marks upon you.”44 As a violation of the law of Moses, such a mark would literally be a “cursed thing” upon the Lamanites’ skin, and visibly signal their rebellion against the Lord’s covenants.45 After Lamanites converted, they would discontinue this practice, and thus future generations lacked the mark: “And their young men and their daughters became exceedingly fair” (3 Nephi 2:15–16).46

The Why

It is easy—even natural—for modern readers of the Book of Mormon to intuitively see contemporary sensibilities regarding race and skin color in passages about a “skin of blackness” or “dark skins,” but such interpretations are misplaced when reading an ancient text. As John W. Welch explained, “when reading ancient historical texts, such as the Book of Mormon, it is absolutely essential not to impose modern ideas of race and cultural identity onto the people of the past.”47 Such interpretations represent what Sam Wineburg refers to as “an anachronistic reading of the past.”48 As Frank Snowden Jr. has observed, “nothing comparable to the virulent color prejudice of modern times existed in the ancient world.”49

Cultural and historical contexts are crucial to overcoming such modern presentist assumptions when reading ancient documents. As Kerry Hull noted, when this is done with the Book of Mormon’s passages describing skin color, it reveals “a more expansive cultural metaphor at play,” while a literal reading “obfuscates the beauty of the figurative imagery and invites unwarranted racial tensions into Nephite/Lamanite relations.”50 It also illustrates, as Welch has concluded, that “there are several explanations for the mark or curse of the Lamanites” that do not involve modern racism.51

Certainly, some among both the Nephites and the Lamanites likely held prejudicial views toward the other group, and descriptions of both groups from the opposing point of view often reflect ancient stereotypes of outsiders.52 These were based not on race, however, but rather on religious, cultural, and tribal differences fueled by costly violent conflicts over the course of nearly a thousand years.53 Furthermore, these occasional expressions of prejudice do not constitute the message of the Book of Mormon, which overwhelmingly extends an inclusive invitation for all people to repent and come unto to Jesus Christ.54

At no point in the Book of Mormon is any individual or group excluded from the blessings of the gospel on the basis of their race or skin color.55 Nephi taught that “the Lord esteemeth all flesh in one” and “denieth none that come unto him, black and white, bond and free, male and female; … and all are alike unto God, both Jew and Gentile.”56 Alma taught that “the Lord will be merciful unto all who call on his name,” and Ammon said, “God is mindful of every people, whatsoever land they may be in” (Alma 9:17; 26:37). According to Mormon, “the gate of heaven is open unto all … who will believe on the name of Jesus Christ” (Helaman 3:28).

At the pinnacle of the Book of Mormon, the Savior Himself states that He was sent “that I might draw all [people] unto me” (3 Nephi 27:14). The sacred volume then ends with an invitation from its final prophet, Moroni, for “all the ends of the earth” to “come unto Christ, and lay hold upon every good gift … and be perfected in him, and deny yourselves of all ungodliness … and love God with all your might, mind and strength, … that by his grace ye may be perfect in Christ; … that ye become holy, without spot” (Moroni 10:24, 30, 32–33).

Through moving historical accounts, the Book of Mormon not only teaches an inclusive message but also illustrates the power of the gospel to break down cultural and ethnic barriers and unite people in Christ. For instance, the record of the sons of Mosiah preaching to the Lamanites provides stirring examples of both Nephites and Lamanites looking past generations of ethnic strife to serve each other and follow Christ.57 One of the most powerful prophetic witnesses of Christ in the book is a Lamanite (Helaman 13–15). At the record’s climax, it demonstrates that the key to overcoming all forms of prejudice is letting go of identities that divide us into “any manner of -ites” and becoming “one, the children of Christ, and heirs to the kingdom of God” (4 Nephi 1:17).

Elder Ahmed Corbitt of the Seventy taught that references to “skin of blackness” or dark skins “should not distract readers from the grand, eternal perspectives and purposes … the Lord intended for the Book of Mormon.” Elder Corbitt powerfully testified,

The Book of Mormon is, in my view, the most racially and ethnically unifying book on the earth. … It teaches that God invites and guides the entire human family toward unity, harmony, and peace, regardless of color or ethnicity. It provides examples of righteous people from contrasting cultures reaching across differences of color and tradition to rescue their brothers and sisters with the gospel of Jesus Christ and with its ordinances and covenants. … The Book of Mormon is a blueprint from heaven, in black and white, for establishing peace on earth in the last days.58

Further Reading

Kerry Hull, “A Soteriology of Robes of Righteousness: Recontextualizing Race and Redemption,” in Jacob: Faith and Great Anxiety, ed. Avram Shannon and George A. Pierce (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2024), 217–272.

T. J. Uriona, “‘Life and Death, Blessing and Cursing’: New Context for ‘Skin of Blackness’ in the Book of Mormon,” BYU Studies 62, no. 3 (2023): 121–140.

Jan J. Martin, “The Prophet Nephi and the Covenantal Nature of Cut Off, Cursed, Skin of Blackness, and Loathsome,” in They Shall Grow Together: The Bible in the Book of Mormon, ed. Charles Swift and Nicholas J. Frederick (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2022), 107–141.

David M. Belnap, “The Inclusive, Anti-discrimination Message of the Book of Mormon,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 42 (2021): 195–370.

Steven L. Olsen, “The Covenant of the Chosen People: The Spiritual Foundations of Ethnic Identity in the Book of Mormon,” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 21, no. 2 (2012): 14–29.

- 1. Newell G. Bringhurst, Saints, Slaves, and Blacks: The Changing Place of Black People within Mormonism, 2nd ed. (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2018), 2. For similar passages, see 1 Nephi 12:23; Jacob 3:5–9; 3 Nephi 2:15–16; Mormon 5:15.

- 2. Gospel Topics, “Race and the Priesthood,” online at churchofjesuschrist.org. For an example of these negative racial connotations’ acceptance, see Rodney Turner, “The Lamanite Mark,” in Second Nephi, The Doctrinal Structure, ed. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1989), 133–157. For historical overviews of how Lamanite skin color and identity have been understood by Latter-day Saints over time, see Armand L. Mauss, All Abraham’s Children: Changing Mormon Conceptions of Race and Lineage (Urbana and Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2003), 114–157; W. Paul Reeve, Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2015), 52–105; Russell W. Stevenson, “Reckoning with Race in the Book of Mormon: A Review of Literature,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 27 (2018): 210–225.

- 3. Richard Lyman Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 97–99, may have been the first to read the text this way, but it has since become a staple of the so-called Americanist school of Book of Mormon studies. See, particularly, the essays in part III, “Indigeneity and Imperialism,” of Elizabeth Fenton and Jared Hickman, eds., Americanist Approaches to The Book of Mormon (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2019), and Jared Hickman, “The Book of Mormon as Amerindian Apocalypse,” American Literature 86 (2014): 429–461. See also Max Perry Mueller, Race and the Making of the Mormon People (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2017), 31–59; Michael Austin, The Testimony of Two Nations: How the Book of Mormon Reads, and Rereads, the Bible (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois, 2024), 54–74. Some who take this approach have been critiqued for neglecting to even acknowledge let alone fairly engage with alternative, non-racialized interpretations of these passages. See Kevin Christensen, “Table Rules: A Response to Americanist Approaches to the Book of Mormon,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 37 (2020): 67–96.

- 4. Jeremy Talmage, “Black, White, and Red All Over: Skin Color in the Book of Mormon,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 28 (2019): 46–68.

- 5. Hugh Nibley, Since Cumorah, 3rd ed.(Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies [FARMS], 1988), 215–216. See alsoHugh Nibley, Lehi in the Desert / The World of the Jaredites / There Were Jaredites (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: FARMS, 1988), 74.

- 6. Nibley, Lehi in the Desert, 73. See also John A. Tvedtnes, “The Charge of ‘Racism’ in the Book of Mormon,” FARMS Review 15, no. 2 (2003): 196, which cites the passage quoted below from the Quran.

- 7. Sura 3:106–107. Seyyed Hossein Nasr, ed., The Study Quran: A New Translation and Commentary (New York, NY: HarperCollins, 2015), 160: “Faces blackening is an Arabic idiom describing a state of distress, shame, or grief. … Conversely, when faces whiten denotes joy and relief and spiritually refers to the light of faith.” Compare Sura 10:26–27: “Unto those who are virtuous shall be that which is most beautiful and more besides. Neither darkness nor abasement shall come over their faces. … And as for those who commit evil deeds, … there will be none to protect them from God. [It will be] as if their faces are covered with dark patches of night.” Sura 39:60: “And on the Day of Resurrection thou wilt see those who lied against God having blackened faces.” Sura 80:38–42: “Faces that Day shall be shining, radiant, laughing, joyous. And faces that Day shall be covered with dust, overspread with darkness. Those, they are the disbelievers, the profligates.” See also Sura 43:17.

- 8. Hugh Nibley, Teachings of the Book of Mormon, Semester One: Transcripts of Lectures Presented to an Honors Book of Mormon Class at Brigham Young University, 1988–1990 (American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications; Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2004), 11, 146, citing A. de Buck, Egyptian Readingbook, vol. 1, Exercises and Middle Egyptian Texts (Leiden, NL: Netherlands Archaeological-Philological Institute, 1948), 73–74. Nibley translates snk.wt as “black of countenance,” which is a somewhat loose, highly contextual translation consistent with the intent of the passage. Gay Robins, “Color Symbolism,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, 3 vols. (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2001), 1:291–294, notes that in Egyptian art and literature, “white was associated with purity … and it could incorporate the notion of ‘light’; thus the sun was said to ‘whiten’ the land at dawn” (p. 291). Deities and kings were sometimes depicted with black skin, “to signify the king’s renewal and transformation,” but in most contexts depictions of black skin were negative. “Within the scheme of Egyptian/non-Egyptian skin color, black was not desirable for ordinary humans, because it marked out figures as foreign, as enemies of Egypt, and ultimately as representatives of chaos” (p. 293).

- 9. See Kerry Hull, “A Soteriology of Robes of Righteousness: Recontextualizing Race and Redemption,” in Jacob: Faith and Great Anxiety, ed. Avram Shannon and George A. Pierce (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2024), 217–272. See also Tvedtnes, “Charge of ‘Racism,’” 195–196.

- 10. As cited in Hull, “Soteriology of Robes,” 237–238; on Augustine, see pp. 247–248. Commenting on Augustine’s use of this same metaphor, Cord J. Whitaker, “Black Metaphors in the King of Tars,” Journal of English and Germanic Philology 112, no. 2 (2013): 176, wrote, “It is clear that the black bride’s whitewashing is purely metaphorical when she says ‘I am black’ in the present tense, although she has already gained her ‘beautiful’ whitewashed status. The bride, inasmuch as she remains black, is a metaphor for the sinner. Inasmuch as she is washed white, she is a metaphor for the sinner who has been saved.”

- 11. Hull, “Soteriology of Robes,” 247–248. Jerome, for instance, wrote, “At one time we were Ethiopians in our vices and sins … our sins had blackened us,” but then after being wash clean of sin by baptism, “We are Ethiopians … who have been transformed from blackness into whiteness.” Cited in Hull, “Soteriology of Robes,” p. 248. Tvedtnes, “Charge of ‘Racism,’” 195, cites a similar example from Ephraim of Syria: “He made disciples and taught, and out of black men he made men white. And the dark Ethiopic women became pearls for the Son.” Note that although these authors were referring to the literal dark or black skin of Ethiopians, they were only using it metaphorically to refer to the spiritual state of people of varying races and skin colors, doing so “without any hint of racial animus against them because of their actual skin color.” Hull, “Soteriology of Robes,” 248.

- 12. T. J. Uriona, “‘Life and Death, Blessing and Cursing’: New Context for ‘Skin of Blackness’ in the Book of Mormon,” BYU Studies 62, no. 3 (2023): 121–140. See also “Is the Book of Mormon ‘Skin of Blackness’ Curse Racist?,” Saints Unscripted, video, 18:03, August 16, 2023, based on a prepublication copy of Uriona’s paper.

- 13. Uriona, “Life and Death, Blessing and Cursing,” 128.

- 14. Vassal Treaty of Esarhaddon, lines 585–587, as translated in Gordon H. Johnston, “Nahum’s Rhetorical Allusions to Neo-Assyrian Treaty Curses,” Bibliotheca Sacra 158 (2001): 432. Uriona, “Life and Death, Blessing and Cursing,” 129n26, also quotes an alternative translation: “May they make your flesh and the flesh of your women, your brothers, your sons and your daughters as black as [bitu]men, pitch and naphtha.”

- 15. Uriona, “Life and Death, Blessing and Cursing,” 136; Johnston, “Nahum’s Rhetorical Allusions,” 432.

- 16. Uriona, “Life and Death, Blessing and Cursing,” 130–135. Johnston, “Nahum’s Rhetorical Allusions,” 432: “This probably depicts the sickly palour that occurs when the life blood flows out of a person’s face at death.”

- 17. Gideon Kotze, Images and Ideas of Debated Readings in the Book of Lamentations (Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck, 2020), 83–84, as cited in Uriona, “Life and Death, Blessing and Cursing,” 137–138.

- 18. 2 Nephi 5:20–21; see 1:17–18, 20, 28–29. Several scholars have noted the covenant context of 2 Nephi 5:21. See especially Uriona, “Life and Death, Blessing and Cursing,” 122–127; Jan J. Martin, “The Prophet Nephi and the Covenantal Nature of Cut Off, Cursed, Skin of Blackness, and Loathsome,” in They Shall Grow Together: The Bible in the Book of Mormon, ed. Charles Swift and Nicholas J. Frederick (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2022), 107–141; Steven L. Olsen, “The Covenant of the Chosen People: The Spiritual Foundations of Ethnic Identity in the Book of Mormon,” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 21, no. 2 (2012): 14–29. For a discussion of this topic in relation to the book of Abraham, see John S. Thompson, “‘Being of that Lineage’: Generational Curses and Inheritance in the Book of Abraham,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 54 (2022): 97–146.

- 19. 1 Nephi 11:13–15; 12:23; 13:15.

- 20. Amy Easton-Flake, “Lehi’s Dream as a Template for Understanding Each Act in Lehi’s Vision,” in The Things Which My Father Saw: Approaches to Lehi’s Dream and Nephi’s Vision, ed. Daniel L. Belnap, Gaye Strathearn, and Stanley A. Johnson (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2011), 179–198; Matthew L. Bowen, “Laman and Nephi as Key-Words: An Etymological, Narratological, and Rhetorical Approach to Understanding Lamanites and Nephites as Religious, Political, and Cultural Descriptors,” (paper presented at the 21st Annual FAIR Conference, Orem, UT, August 7–9, 2019), online at fairlatterdaysaints.org.

- 21. Olsen, “Covenant of the Chosen People,” 20–21, 26. See also Jan J. Martin, “Filthy This Day Before God: Jacob's Use of Filthy and Filthiness in His Nephite Sermons,” in Jacob, 191–216.

- 22. See David M. Belnap, “The Inclusive, Anti-discrimination Message of the Book of Mormon,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 42 (2021): 299–301, table 3, for a comprehensive list of examples. For additional discussion citing numerous examples from the text see Hull, “Soteriology of Robes,” 230–243; Douglas Campbell, “‘White’ or ‘Pure’: Five Vignettes,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 29, no. 4 (1996): 119–135; Michael R. Ash, Shaken Faith Syndrome: Strengthening One’s Testimony in the Face of Criticism and Doubt, 2nd ed. (Redding, CA: FAIR, 2013), 290–301.

- 23. Belnap, “Inclusive, Anti-discrimination Message,” 212.

- 24. The wording of “a white and a delightsome people” follows the printer’s manuscript (this passage is not extant in the original manuscript). See Royal Skousen and Robin Scott Jensen, eds., Revelations and Translations, vol. 3, pt. 1, Printer’s Manuscript of the Book of Mormon, 1 Nephi 1–Alma 35 (Salt Lake City, UT: Church Historian’s Press, 2015), 201; Grant Hardy, ed., The Annotated Book of Mormon (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2023), 162, note on 2 Nephi 30:3, 6.

- 25. Book of Mormon Central, “What Does It Mean to Be a White and Delightsome People? (2 Nephi 30:6),” KnoWhy 57 (March 18, 2016); Royal Skousen, Analysis of Textual Variants of the Book of Mormon, 2nd ed., 6 parts (Provo, UT: BYU Studies and FARMS, 2017), 2:933–936; Hardy, Annotated Book of Mormon, 162, note on 2 Nephi 30:6. Since the imagery in 2 Nephi 30:6 is a reversal of 2 Nephi 5:21, it is interesting that it speaks of metaphorical “scales of darkness” instead of “skins of blackness.” Adam Oliver Stokes, “‘Skins’ or ‘Scales’ of Blackness? Semitic Context as Interpretative Aid for 2 Nephi 4:35 (LDS 5:21),” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 27 (2018): 278–289, proposed that both “skin” and “scales” could be translations of the same underlying Semitic term since the Hebrew and Aramaic root for “skin” (ʾwr) is also used for the scales of a snake and husks of grain—both of which can be shed. This suggests that both the “skins of blackness” and “scales of darkness” should be understood as metaphors for a spiritual darkness or blackness that can be shed with repentance.

- 26. Brant A. Gardner, Traditions of the Fathers: The Book of Mormon as History (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2015), 161: “If Lamanites and Nephites were as visually distinct as black and white skins would have made them, we should see descriptions in the text where that distinction is noted. It never happens.” See alsoBrant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 6 vols. (Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 2:116–117; Gerrit M. Steenblik, “Demythicizing the Lamanites’ ‘Skin of Blackness,’” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 49 (2021): 213–219.

- 27. John L. Sorenson, An Ancient American Setting for the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: FARMS, 1985), 90. He also rhetorically asks, “What about the ‘dark skin’ of the Lamanites and the ‘fair skin’ of the Nephites? In the first place, the terms are relative. How dark is dark? How white is fair? … [We] may doubt that it was as dramatic [of a difference] as the Nephite recordkeepers made out” (pp. 89, 91). Robins, “Color Symbolism,” 293, similarly noted: “Although undoubtedly some Egyptians’ skin pigmentation differed little from that of Egypt’s neighbors, in the Egyptian worldview foreigners had to be plainly distinguished. Thus, Egyptian men had to be marked by a common skin color that contrasted with images of non-Egyptian men.”

- 28. Hardy, Annotated Book of Mormon, 101, note on 2 Nephi 5:21: “The most plausible naturalistic explanation is that they intermarried with indigenous inhabitants of the Americas.”See also Eugene England, “‘Lamanites’ and the Spirit of the Lord,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 18, no. 4 (1985): 30; John A. Tvedtnes, “Unanswered Questions in the Book of Mormon,” in The Most Correct Book: Insights from a Book of Mormon Scholar (Salt Lake City, UT: Cornerstone, 1999), 317; Nibley, Teachings of the Book of Mormon, 146–147; John L. Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex: An Ancient American Book (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2013), 293. On skin tone and sun exposure, compare Song of Solomon 1:6: “I am black, because the sun hath looked upon me.” Uriona, “Life and Death, Blessing and Cursing,” 140, put forward another proposal that could be related to the lifestyle of the Lamanites, suggesting that “this phrase [‘skin of blackness’] might speak to conditions such as Job’s diseased skin,” referring to Job 30:30 (“My skin is black upon me”). In a forthcoming manuscript, Uriona suggests such a disease could have spread among the Lamanites due to their lifestyle of eating raw meat, making them more subject to diseases and parasites. The video “Is the Book of Mormon ‘Skin of Blackness’ Curse Racist?,” which is based on Uriona’s work, notes that many of the curses listed in Deuteronomy 28 are skin diseases and are said to be “upon thee for a sign and for a wonder, and upon thy seed for ever” (Deuteronomy 28:46). The Hebrew word for “sign” is the same word translated “mark” in Genesis 4:15.

- 29. England, “Lamanites,” 30; emphasis added. Compare Hull, “Soteriology of Robes,” 245: “For Mormon, writing a full thousand years after the declaration of the curse, this self-administered marking of the skin was an outward symbol of the curse. The mark was not the curse itself but a physical, self-imposed identifier of those ‘out of the covenant,’ those on whom the curse had previously fallen.”

- 30. Nibley, Lehi in the Desert, 74. Steenblik, “Demythicizing,” 194–196, points out the prophets in the Hebrew Bible and the Book of Mormon often portray the Lord as the one who enacted events more directly by human actions.

- 31. John W. Welch, “Mosiah 29–Alma 4,” in John W. Welch Notes (Springville, UT: Book of Mormon Central, 2020), 540; Ethan Sproat, “Skins as Garments in the Book of Mormon: A Textual Exegesis,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 24, no. 1 (2015): 138–165. See also Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Book of Mormon Prophets Discourage Nephite-Lamanite Intermarriage? (Alma 3:8),” KnoWhy 110 (May 30, 2016).

- 32. Welch, “Mosiah 29–Alma 4,” 540.

- 33. Sproat, “Skins as Garments,” 149–158. Sproat notes that 2 Nephi 5:21–25, Jacob 3:5–9, and Alma 3:5–6 all originate within a covenant or temple context, while 3 Nephi 2:15–16 is describing Lamanites converting to Nephite religion and thus gaining access to the white garment-skins of their temple tradition. See pp. 149–150, 153–157, 160.

- 34. Hull, “Soteriology of Robes,” 217–240. See also Stephen D. Ricks, “The Garment of Adam in Jewish, Muslim, and Christian Tradition,” in Temples of the Ancient World, ed. Donald W. Parry (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: FARMS, 1994), 705–739; Hugh Nibley, “Sacred Vestments,” in Temple and Cosmos (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: FARMS, 1992), 91–138. Since the mark is associated with and in some cases is identified as the curse upon the Lamanites, Hull’s discussion of curse-oaths as something “worn” on the skin like a tight garment in some ancient Near Eastern cultures is also interesting in light of the skins-as-garments theory. Hull, “Soteriology of Robes,” 244–246.

- 35. Steenblik, “Demythicizing,” 179–190, quote on p. 181. Gardner, Traditions of the Fathers, 163–164, also mentions Mesoamerican body painting not as a possible explanation of the mark or dark skins but to counter misunderstandings caused by previous attempts to use depictions of the darkened bodies as evidence of literal skin color difference.

- 36. Steenblik, “Demythicizing,” 192, 206–208. Hull, “Soteriology of Robes,” 246, notes the similar Hittite practice of rubbing oil on one’s skin while muttering curses.

- 37. William Saturno, Franco D. Rossi, David Stuart, and Heather Hurst, “A Maya Curia Regis: Evidence for a Hierarchical Specialist Order at Xultun, Guatemala,” Ancient Mesoamerica 28, no. 2 (2017): 7. See also Jerry D. Grover Jr., Evidence of the Nehor Religion in Mesoamerica (Provo, UT: Challex Scientific Publishing, 2017), 6. Steenblik, “Demythicizing,” 204, only suggests that 3 Nephi 2:11–15 may refer to Lamanites renouncing the use of body paint.

- 38. Martin, “Prophet Nephi,” 122–125; Clifford P. Jones, “Understanding the Lamanite Mark,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 56 (2023): 171–258.

- 39. Martin, “Prophet Nephi,” 122–123; Hull, “Soteriology of Robes,” 268n136.

- 40. Jones, “Understanding the Lamanite Mark,” 206–208. See also J. Eric S. Thompson, “Tattooing and Scarification among the Maya,” in The Carnegie Maya III: Carnegie Institution of Washington Notes on Middle American Archaeology and Ethnology, 1940–1957, comp. John M. Weeks (Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado, 2011),250–253; Michael D. Coe and Stephen Houston, The Maya, 10th ed. (New York, NY: Thames and Hudson, 2022), 167, 274.

- 41. Thompson, “Tattooing and Scarification,” 253.

- 42. Hull, “Soteriology of Robes,” 268n136.

- 43. Cecil H. Brown, “Hieroglyphic Literacy in Ancient Mayaland: Inferences from Linguistic Data,” Current Anthropology 32, no. 4 (1991): 489–496.

- 44. Jones, “Understanding the Lamanite Mark,” 182–184; Francis Brown, S. R. Driver, and Charles A. Briggs, The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2007), 891.

- 45. Jones, “Understanding the Lamanite Mark,” 185–186, 188–197.

- 46. Jones, “Understanding the Lamanite Mark,” 210–214, 237, argues that 3 Nephi 2:12–16 refers to the Lamanite converts in Helaman 5:50–51 and that thus a generation (forty-two years) had already passed by time they are described as becoming “white.” Compare Hardy, Annotated Book of Mormon, 101, note on 2 Nephi 5:21, and 565, note on 3 Nephi 2:14–16.

- 47. Welch, “Mosiah 29–Alma 4,” 539.

- 48. Sam Wineburg, Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts: Charting the Future of Teaching the Past (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2001), 104. See also Jones, “Understanding the Lamanite Mark,” 215–217, 227; Hull, “Soteriology of Robes,” 249–251. This is not uniquely a Book of Mormon problem, as many scholars have similarly noted the problem of anachronistically reading race into other ancient Near Eastern, classical Greco-Roman, and medieval European sources. See Frank M. Snowden Jr., Blacks in Antiquity: Ethiopians in Greco-Roman Experience (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1970); Frank M. Snowden Jr., “Europe’s Oldest Chapter in the History of Black-White Relations,” in Racism and Anti-racism in World Perspectives, ed. Benjamin P. Bowser (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1995), 3–26; David M. Goldenberg, The Curse of Ham: Race and Slavery in Early Judaism, Christianity, and Islam (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003); Rodney Steven Sadler Jr., Can a Cushite Change His Skin? An Examination of Race, Ethnicity, and Othering in the Hebrew Bible (New York, NY: T&T Clark, 2005); Ran HaCohen, “The ‘Jewish Blackness’ Thesis Revisited,” Religions 9, no. 2 (2018): 1–9.

- 49. Frank M. Snowden Jr, Before Color Prejudice: The Ancient View of Blacks (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1983), 63.

- 50. Hull, “Soteriology of Robes,” 231.

- 51. Welch, “Mosiah 29–Alma 4,” 540.

- 52. Dieter F. Uchtdorf, “What Is Truth?” (Brigham Young University devotional, January 13, 2013), explained: “In the Book of Mormon, both the Nephites as well as the Lamanites created their own ‘truths’ about each other. The Nephites’ ‘truth’ about the Lamanites was that they ‘were a wild, and ferocious, and a blood-thirsty people,’ never able to accept the gospel. The Lamanites’ ‘truth’ about the Nephites was that Nephi had stolen his brother’s birthright and that Nephi’s descendants were liars who continued to rob the Lamanites of what was rightfully theirs. These ‘truths’ fed their hatred for one another until it finally consumed them all. Needless to say, there are many examples in the Book of Mormon that contradict both of these stereotypes. Nevertheless, the Nephites and Lamanites believed these ‘truths’ that shaped the destiny of this once-mighty and beautiful people.” For ancient examples of stereotyping similar to Book of Mormon examples, see Tvedtnes, “Charge of ‘Racism,’” 189–190, which cites both ancient Mesopotamian stereotypes of Amorites and Aztec stereotypes of the Otomi as similar examples to stereotypes of Lamanites in the Book of Mormon. See also Sorenson, Ancient American Setting, 89–91; Hull, “Soteriology of Robes,” 242–243.

- 53. Nibley, Lehi in the Desert, 74; Nibley, Since Cumorah, 216; Hull, “Soteriology of Robes,” 231; Welch, “Mosiah 29–Alma 4,” 540.

- 54. This is demonstrated with exhaustive detail in Belnap, “Inclusive, Anti-discrimination Message,” 195–370. See also Tvedtnes, “Charge of ‘Racism,’” 183–197.

- 55. For a comprehensive list of relevant passage expressing the inclusive gospel message, see Belnap, “Inclusive, Anti-discrimination Message,” 301–306, table 4.

- 56. 1 Nephi 17:35; 2 Nephi 26:33, emphasis added. Steenblik, “Demythicizing,” 205, and Gardner, Second Witness, 2:374–374, argue that this instance of “black and white” should, in fact, be interpreted as literal skin color. Belnap, “Inclusive, Anti-discrimination Message,” 206n30, cites Marvin Perkins in suggesting that this passage is consistent with the symbolism of black and white throughout the text but that nonetheless, “all ethnicities are covered by ‘Jew and Gentile’ at the end of that verse.” Whatever “black and white” means here, the sentiment of the passage is that all people, regardless of race, nationality, gender, and so on, are “alike unto God.” As Belnap notes, “the principle is true that God does not discriminate by skin color, and both sinners and righteous people have access to God.”

- 57. Mosiah 28:1–9; Alma 17–27. See discussion in Belnap, “Inclusive, Anti-discrimination Message,” 259–263.

- 58. Ahmad Corbitt, “He Denieth None That Come unto Him: A Personal Essay on Race and the Priesthood, Part 3,” online at history.churchofjesuschrist.org. He added: “I believe that God is all-knowing—that He knew long ago of ‘calamity [that would] come upon the inhabitants of the earth,’ including pervasive ethnic and racial strife. He also knew that advancements in technology would lead to unprecedented multiracial and multiethnic interaction among His children in our modern world—the so-called ‘global village.’ I believe that with this foreknowledge, God prepared the Book of Mormon to, among other things, guide His children of different colors and cultures as we navigate these unique challenges and opportunities in search of universal unity and peace. … I believe, therefore, that another way of saying that the Book of Mormon gathers scattered Israel is to say that it invites and unifies people of all races and ethnicities as brothers and sisters. It unites all peoples who accept the gospel in a common covenant with God, our Eternal Father, and Jesus Christ, our universal Savior.”

KnoWhy Citation

Related KnoWhys

Subscribe

Get the latest updates on Book of Mormon topics and research for free