You are here

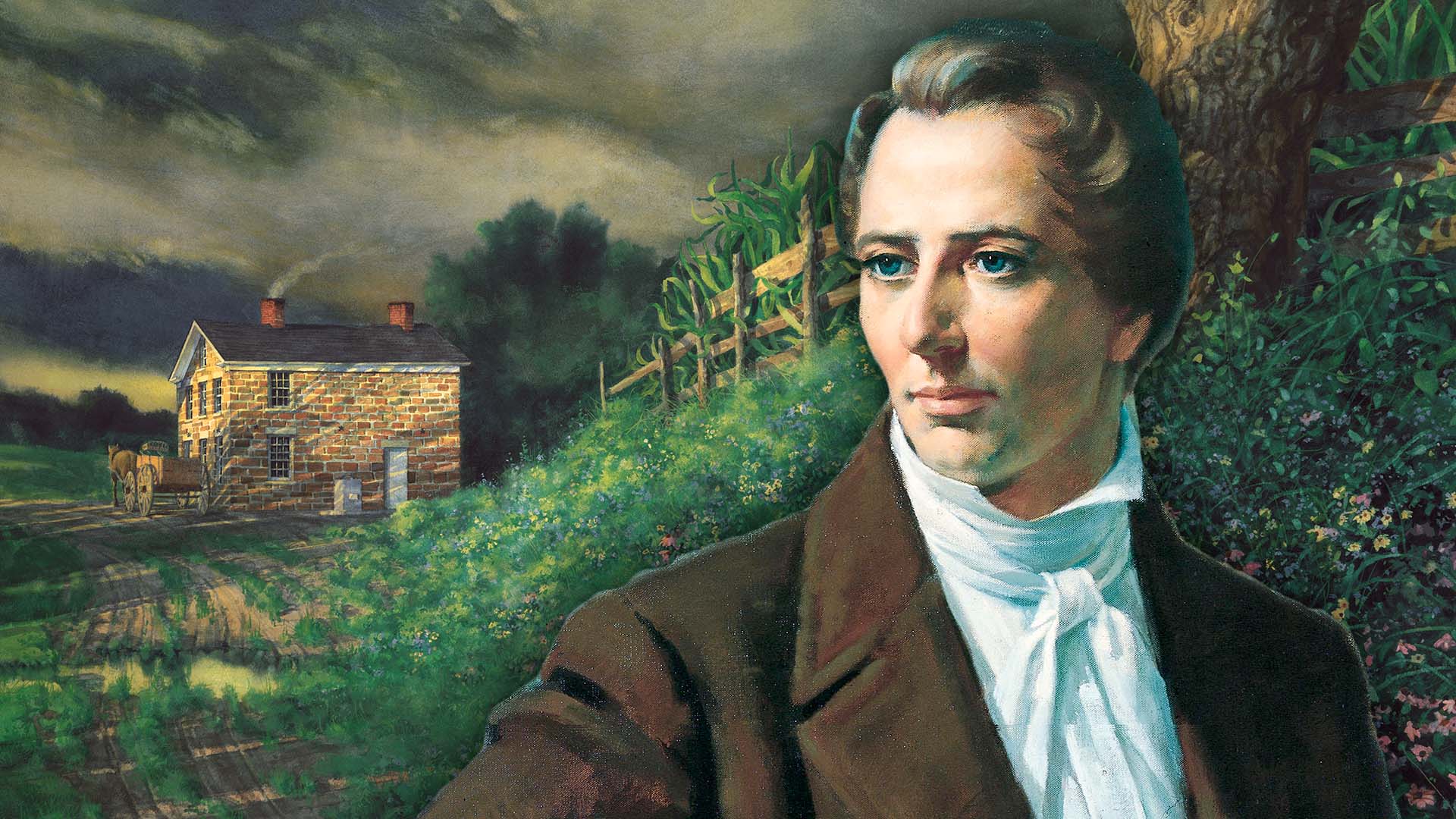

Why was Joseph Smith Murdered?

Doctrine and Covenants 135:1, 7

The Know

On June 27, 1844, Joseph Smith and his brother, Hyrum, were butchered by a mob in Carthage Jail. This was not a spontaneous or unexpected event—Joseph himself anticipated that he went “as a lamb to the slaughter” (Doctrine and Covenants 135:4) and had in fact feared for his life for at least several months, perhaps longer. And he had good reason to fear—there was, in fact, a murderous plot to have him and his brother kidnapped and killed.

According to the recent analysis of legal scholar Joseph I. Bentley, the key Nauvoo apostates were a trio of brothers, William and Wilson Law, Robert and Charles Foster, and Francis and Chauncey Higbee. They colluded with prominent anti-Mormons such as Thomas Sharp, a newspaper editor in the nearby town of Warsaw, Illinois. Whether or not they hatched “a well-planned conspiracy,” Bentley argues, “they undoubtedly went forward, acting deliberately and concertedly.”1 They acted through a series of “legal maneuvers” that were “intentionally designed … for the purpose of placing Joseph Smith’s life in mortal danger in Carthage.”2

By early 1844, the plan was to file legal charges against Joseph and Hyrum in Carthage, Illinois—the location of the Hancock County Circuit Court—thereby forcing Joseph out of his stronghold in Nauvoo to address the legal matters. At one point, Dan Jones overheard the leaders of this group “say that they did not expect to prove anything against [Joseph], but that they had eighteen accusations against him, and that as one failed they would try another to detain him” in Carthage.3 Once they were detained, anti-Mormon mobs whipped up into a frenzy by the charged rhetoric published by Sharp and others would seize the opportunity to execute the Prophet and his brother in an act of what they perceived as “vigilante justice.”

This plan was put into action as early as February 26, 1844, when the Law brothers and their collaborators instituted or appealed a series of lawsuits to Carthage. Already at this point, Joseph suspected a darker plot at work than merely resolving legal differences.4 After those lawsuits were consolidated and dismissed, the dissenters initiated additional legal suits in May. Eventually, some of these were successful in getting Joseph out of Nauvoo, and thus he was in Carthage on May 27, 1844, exactly one month before his martyrdom. On that occasion, Charles Foster—one of the conspirators—evidently had a temporary change of heart and notified Joseph of a plan to have him assassinated the next day. With this advance notice, Joseph was able to muster “enough well-armed troops … from Nauvoo to guarantee Joseph’s protection,” and he subsequently returned home safely.5

Meanwhile, Thomas Sharp had been agitating against Joseph and stoking the anti-Mormon fires in his newspaper, the Warsaw Signal. On May 29, he published an editorial declaring, “We have seen and heard enough to convince us that Joe Smith is not safe out of Nauvoo, and we would not be surprised to hear of his death by violent means in a short time. He has deadly enemies …. The feeling of this country is now lashed to its utmost pitch, and will break forth in fury upon the slightest provocation.”6 A little over a week later, the Nauvoo dissenters, who had formed their own church, launched their own newspaper, the Nauvoo Expositor, encouraging Church members to come join with them and publishing inflammatory content about Joseph and the Church from within Nauvoo.7

The first and only issue of the Expositor was published on June 7, 1844. After two days of extensive deliberations, the Nauvoo City Council—which included Joseph Smith and 17 other high-profile leaders of the Church—declared the paper a public nuisance (as they were legally authorized to do by the Nauvoo Charter) and ordered both the printing press and copies of the newspaper to be peacefully destroyed. Although this runs counter to present-day notions of the freedom of the press secured in the First Amendment of the US Constitution, the actions of Joseph and the council were legally sound and not unusual for the time.8 Other presses had been similarly treated in Springfield and Alton, Illinois, and also, of course, in Independence, Missouri.

Nonetheless, the action generated an uproar throughout the county thanks to anti-Mormon agitators, and the owners of the Expositor reacted by filing charges at Carthage—not for violating their freedom of the press, but allegedly for instigating a “riot.” Joseph initially used a writ of habeas corpus to get the case tried before the Nauvoo Municipal Court, which cleared him and the other 17 defendants of all charges.9 Naturally, this only served to further stoke anti-Mormon fervor as Joseph’s critics felt he had used his “home court” to evade justice.

On the advice of Jesse Thomas, the presiding circuit court judge in Carthage, Joseph and the others submitted to a second trial of the riot charge, this time outside Nauvoo before Justice Daniel H. Wells, a reputable non-Latter-day Saint justice of the peace living just outside Nauvoo. “After a long hearing, with examination and cross-examination of five witnesses for each side, all defendants were again discharged,” but this “failed to satisfy the agitated neighbors.”10

Resolutions from mass meetings instigated by Thomas Sharp and the Expositor publishers “called for the invasion of Nauvoo and extermination of all Mormons.”11 Sharp and others held rallies in their towns, fanned the flames with appearances by the Nauvoo apostates, and declared June 19 the date for the invasion of Nauvoo by several local militias. In reaction to this threat, Joseph declared martial law in Nauvoo, calling out the Nauvoo Legion to protect the city from invasion. The threatened invasion never came, and after Governor Ford met with Joseph’s enemies in Warsaw and Carthage, he insisted that Joseph come to Carthage to stand trial yet again for the riot charge. The Governor guaranteed Joseph that he would be protected. However, he insisted on disarming the Nauvoo Legion in order to keep the peace, but did not disarm the other militias at the same time.

Once in Carthage, Joseph and other defendants were arraigned on the riot charge and posted bail when the Higbees deliberately failed to present witnesses and asked for their case to be rescheduled for September. Before Joseph and Hyrum could leave Carthage, however, they were charged with treason for having declared martial law—yet another legal charge that lacked any legal merit, but was useful because treason was a non-bailable offense. This prevented Joseph and Hyrum from leaving, and left them trapped in Carthage Jail, vulnerable to mob action.

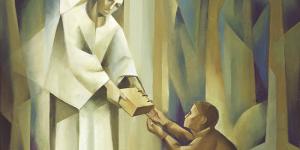

Inside the jail, Hyrum read from the book of Ether in the Book of Mormon and Joseph bore a strong testimony to the guards of the truthfulness of the Restoration, of the Book of Mormon, and of the visitations of angels. Outside, the mob, eventually numbering about 2,000, was able to mobilize, with people standing ready to join from Missouri, and then come to Carthage and assassinate Joseph and Hyrum late in the afternoon of June 27, 1844.12

The Why

As Dallin H. Oaks (a legal scholar before being called as an apostle) and Marvin S. Hill wrote, “The murder of Joseph and Hyrum Smith at Carthage, Illinois, was not a spontaneous, impulsive act by a few personal enemies of the Mormon leaders, but a deliberate political assassination, committed or condoned by some of the leading citizens in Hancock County.”13 Nauvoo was the largest city in Illinois at the time, and Joseph was the mayor and a presidential candidate.14 Hyrum was vice mayor and running for office in the state legislature. Politically, they were “two of the most influential men in Illinois” at the time.15 As such, their assassinations are not only important to Latter-day Saint history, but also the history of the state of Illinois.

The men who colluded together to kill Joseph and Hyrum had a diverse and complex set of motives for their actions—thus understanding why these two influential leaders were murdered is complex and involves numerous different factors. As Bentley explains:

Many factors contributed to the Prophet’s murder on June 27, 1844. Among these were fear of the Nauvoo Legion’s power; perceived abuses related to powers granted under the Nauvoo Charter; political unrest caused by the rapidly increasing Mormon population in Hancock County, Illinois, and Lee County, Iowa; economic competition with some of the leading Mormon opponents; persisting grudges among some Missourians; rumors distorting the beginnings of the limited practice of plural marriage; criticism of Joseph Smith’s presidential campaign; and the concentration of legislative, judicial, executive, military, and religious power in one man, Joseph Smith.16

No doubt, for each of the principal conspirators, one or more of these factors played a role in their decision to plot cold-blooded murder. Joseph and Hyrum, meanwhile, went to their deaths nobly and with a clear conscience (D&C 135:4). In the immediate wake of their deaths, John Taylor wrote:

Joseph Smith, the Prophet and Seer of the Lord, has done more, save Jesus only, for the salvation of men in this world, than any other man that ever lived in it. In the short space of twenty years, he has brought forth the Book of Mormon, which he translated by the gift and power of God, and has been the means of publishing it on two continents; has sent the fulness of the everlasting gospel, which it contained, to the four quarters of the earth; has brought forth the revelations and commandments which compose this book of Doctrine and Covenants, and many other wise documents and instructions for the benefit of the children of men; gathered many thousands of the Latter-day Saints, founded a great city, and left a fame and name that cannot be slain. He lived great, and he died great in the eyes of God and his people; and like most of the Lord’s anointed in ancient times, has sealed his mission and his works with his own blood; and so has his brother Hyrum. In life they were not divided, and in death they were not separated! (D&C 135:3)

As Elder Jeffrey R. Holland observed, their willingness to ultimately go their deaths with steadfast faith in the work they had accomplished stands as a potent witness to the truthfulness of the Restoration.17

Further Reading

Joseph I. Bentley, “Road to Martyrdom: Joseph Smith’s Last Legal Cases,” BYU Studies 55, no. 2 (2016):

Dallin H. Oaks, “The Suppression of the Nauvoo Expositor,” Utah Law Review 9 (1965): 862–903; republished in slightly abbreviated form as “Legally Suppressing the Nauvoo Expositor in 1844,” in Sustaining the Law: Joseph Smith's Legal Encounters, ed. Gordon A. Madsen, Jeffrey N. Walker, and John W. Welch (Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 2014), 427–459.

Dallin H. Oaks and Marvin S. Hill, Carthage Conspiracy: The Trail of the Accused Assassins of Joseph Smith (Chicago and Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1979).

- 1. Joseph I. Bentley, “Road to Martyrdom: Joseph Smith’s Last Legal Cases,” BYU Studies 55, no. 2 (2016): 26.

- 2. Bentley, “Road to Martyrdom,” 12. In sworn testimony, several witnesses—including Joseph and Hyrum Smith—later asserted that William Law had colluded with Missourians two years before the murder to have Joseph kidnapped back to Missouri where he could be killed. See Bentley, “Road to Martyrdom,” 25–26 n.87.

- 3. Dan Jones, “The Martyrdom of Joseph Smith and His Brother, Hyrum!,” trans. and ed. Ronald D. Dennis, BYU Studies 24, no. 1 (1984): 97.

- 4. Bentley, “Road to Martyrdom,” 27–28.

- 5. Bentley, “Road to Martyrdom,” 29.

- 6. Warsaw Signal, May 29, 1844, as cited in Bentley, “Road to Martyrdom,” 30.

- 7. Bentley, “Road to Martyrdom,” 30.

- 8. See Dallin H. Oaks, “The Suppression of the Nauvoo Expositor,” Utah Law Review 9 (1965): 862–903; republished in slightly abbreviated form as “Legally Suppressing the Nauvoo Expositor in 1844,” in Sustaining the Law: Joseph Smith's Legal Encounters, ed. Gordon A. Madsen, Jeffrey N. Walker, and John W. Welch (Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 2014), 427–459. See also Bentley, “Road to Martyrdom,” 30–39. Joseph and the city council were legally liable for the lost property for destroying the press, but that was a matter of civil (rather than a criminal) law.

- 9. See Bentley, “Road to Martyrdom,” 41–43. See also Jeffrey N. Walker, “Invoking Habeas Corpus in Missouri and Illinois,” in Sustaining the Law, 357–399.

- 10. Bentley, “Road to Martyrdom,” 45.

- 11. Bentley, “Road to Martyrdom,” 45.

- 12. This is all summarized from Bentley, “Road to Martyrdom,” 46–53, 62–72.

- 13. Dallin H. Oaks and Marvin S. Hill, Carthage Conspiracy: The Trail of the Accused Assassins of Joseph Smith (Chicago and Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1979), 46.

- 14. On Joseph Smith’s presidential campaign, see Spencer W. McBride, Joseph Smith for President: The Prophet, the Assassins, and the Fight for American Religious Freedom (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2021); Derek R. Sainsbury, Storming the Nation: The Unknown Contributions of Joseph Smith’s Political Missionaries (Provo, UT: BYU Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2020).

- 15. Oaks and Hill, Carthage Conspiracy, 4–5.

- 16. Bentley, “Road to Martyrdom,” 11.

- 17. See Jeffrey R. Holland, “Safety for the Soul,” Ensign, November 2009, 88–90. See also Book of Mormon Central, “An Apostle's Witness (2 Nephi 33:11),” KnoWhy 2 (January 2, 2016).

KnoWhy Citation

Related KnoWhys

Subscribe

Get the latest updates on Book of Mormon topics and research for free