You are here

Why is Amulek’s Household Significant?

Alma 10:7

The Know

Alma’s first attempt to preach the gospel in the city of Ammonihah was a failure. The people, Mormon recorded, “withstood all [of Alma’s] words, and reviled him, and spit upon him, and caused that he should be cast out of their city” (Alma 8:13). After being prompted by an angel, Alma returned to the apostate city to once again call its inhabitants to repentance (vv. 14–18). Upon returning, Alma found a supporter in the form of Amulek who had been instructed in vision to protect Alma (vv. 20–21).

Amulek was especially grateful for Alma’s blessing over his household, proclaiming, “He hath blessed mine house, he hath blessed me, and my women, and my children, and my father and my kinsfolk; yea, even all my kindred hath he blessed, and the blessing of the Lord hath rested upon us according to the words which he spake” (Alma 10:11).

Amulek specifically mentioning his women, children, father, and kinsfolk as being part of his household provides interesting insight into the social structure of Book of Mormon societies and peoples. Far from the nuclear families prevalent today (consisting of parents and children), this added detail “suggests an interesting pattern of kin connections” known in many ancient cultures, including ancient Mesoamerica.1

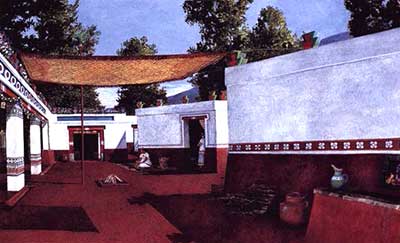

“For kin-based societies,” one Book of Mormon scholar noted, “a literal house typically symbolizes the family. Groups of kin frequently live in compounds.” This is suggested by Amulek’s usage of “mine house” to describe his immediate and extended kindred.

Indeed, “It seems likely Amulek’s ‘house’ was a typical Mesoamerican compound. When Amulek speaks of Alma blessing his ‘house’ and then lists specific relatives, these are almost certainly people living in the same ‘house’ or compound, not a single structure.”2

This picture in the Book of Mormon not only converges well with ancient Israelite and eastern Mediterranean family structures,3 but also the archaeological record, which verifies such household compounds existing during the pre-Classic Maya period.4

One oddity in Amulek’s description is his mentioning “my women” as being part of his household. Could he have meant female relatives such as sisters or cousins? Perhaps, but a stronger possibility, as suggested by John A. Tvedtnes, is that Amulek was referring to his wives. As Tvedtnes noted, the Book of Mormon uses the word “woman” to refer to a “wife.”5 If Alma 10:11 is read this way, then it would make Amulek a polygamist.

All of this makes sense. Amulek, after all, was said to have been “a man of no small reputation among” the people of Ammonihah who had “many kindreds and friends” and “much riches” (Alma 10:4). This is consistent with ancient polygamy, which was almost exclusively practiced by wealthy social elites who could afford to support large families, “a small fraction only making use of the privilege.”6 It is also consistent with how the Book of Mormon elsewhere depicts polygamy.7

The Why

The description of Amulek’s household is not mere trivia. Later in the account, Alma and Amulek were forced to witness the horrendous execution of those who believed their preaching. This included women and children, and apparently members of Amulek’s own family (Alma 14:8–15). By describing his family earlier in the account, the narrative deeply humanizes Amulek and his anguish.

Amulek went from being one of Ammonihah’s social elites to losing everything—his reputation, his social status, his riches, and even his family— for the gospel’s sake. The victims themselves were martyrs for the gospel. As John W. Welch explained, the rulers of Ammonihah “burn[ed] the women and children in Ammonihah . . . because they [themselves] had believed . . . having been taught to believe in Alma’s preaching of the word of God.”8

By first coming to know Amulek and his family, readers are able to empathize with them when the narrative makes a tragic turn for the worst. The stakes in this account are heightened, and Amulek’s plea to Alma to save the victims—including his own family—from martyrdom is given far more compelling moral and emotional weight (Alma 14:10).

Further Reading

Stephen D. Ricks, “A Note on Family Structure in Mosiah 2:5,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 6 (2013): 9–10.

John W. Welch, The Legal Cases in the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press and The Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2008), 237–271.

Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 4:164–17.

- 1. Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 4:168.

- 2. Gardner, Second Witness, 4:169.

- 3. Stephen D. Ricks, “A Note on Family Structure in Mosiah 2:5,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 6 (2013): 9–10.

- 4. Gardner, Second Witness, 4:169.

- 5. John A. Tvedtnes, “The Hebrew Background of the Book of Mormon,” in Rediscovering the Book of Mormon, ed. John L. Sorenson and Melvin J. Thorne (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1991), 91.

- 6. Ze’ev W. Falk, Hebrew Law in Biblical Times, 2d ed. (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, and Winona Lake, IN, 2001), 127–29, 190.

- 7. See Book of Mormon Central, “What Does the Book of Mormon Say About Polygamy? (Jacob 2:30),” KnoWhy 64 (March 28, 2016).

- 8. John W. Welch, The Legal Cases in the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press and The Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2008), 262.

KnoWhy Citation

Related KnoWhys

Subscribe

Get the latest updates on Book of Mormon topics and research for free